Omniae fabulae in tres pars divisa sunt

Everything

comes in threes, did you ever notice?

Partly, this is because after three we stop counting, but

partly because three is the least number that lends stability. Consider a two-legged stool. What about a bicycle, TOF hears you say. Ah, but there is a third wheel: the gear

wheel connected by a chain to the rear wheel. Ah-ha!

The three parts

of a story are the Beginning, the Body, and… but you’re way ahead of

me. Yes, you have leapt to a Conclusion. The Laws of Interest apply to

all three

parts, but they apply to each part differently, because, you guessed it,

there

are three kinds of Interest.

- Curiosity. What is going on here? Capture the interest.

- Suspense. What will happen next? Sustain the interest.

- Satisfaction. So that’s what it all meant. Resolve the interest.

TOF will leave

it as an exercise to Constant Reader to determine which sort of interest

applies to each principle part of a Story.

Curiosity Kills Cats, Not Readers

The Beginning

captures the reader’s interest by eliciting Curiosity, a desire to know more. In The Twenty Problems of the Fiction Writer (1929), John Gallishaw lists seven overlapping ways to

capture interest in the Beginning of the Story: |

Only Twenty?

|

-

A Title that is arresting, suggestive,

and challenging.

-

A Story Situation. Some feat to be

accomplished or some course of

conduct to be chosen.

- The Explanatory Matter. The conditions precipitating the Story

Situation, including:

- Importance of the Story Situation,

intrinsically or synthetically

-

Something unusual in the Story Situation or in the

character of the Chief Actor

- Originality of conception or interpretation

so that the apparently usual is made unusual.

-

A contrast or juxtaposition of opposites.

-

The foreshadowing of difficulty, conflict,

or disaster to carry interest over into the Body of the Story.

They are numbered for convenience. Please do not try to insert them in your prose in sequence. But we can order them in our minds, if not on the page. Let’s consider them, one by one.

1. Titles.

What

we know first about anything is its being, its existence; and so we

give it a name so we can talk about it. Adam spent a lot of time in Eden doing this: "That's an antelope. That's a pomegranate...." before he realized he had not yet said "That's a hot chick" and fell into a depression. What we know first about any

story or novel is its title. Before the reader knows the names of the

characters, he knows the name of their story. In fact, the latter may

be a precondition to the former, since a poor title can drive readers

off. If the Bible were entitled War Gods of the Desert, more people might read it.

Well-known writers may get by with so-so titles. Their books will

sell regardless. And some readers will buy anything in their favorite

genre or series, and again the title will not be the deciding factor. But for

the most part, a book will sit among other books, each clamoring for

attention. The browsing reader, who is neither fan nor fanatic, will

pick up one and not the other.

Why? The title, the cover, and the opening passages. Now short

stories seldom have covers, and even for novels the cover is usually not

controlled by the writer. So let’s consider titles, as such.

What are the Qualities of a Good Title?

A title, says Gallishaw, should be Arresting, Suggestive, and Challenging.

1. Arresting. To arrest is to "cause to stop." In this case, the reader is caused to stop with book in hand and consider it further. What the heck is this about? Especially

arresting titles include When the Sacred Gin Mill Closes

(Lawrence Block); “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones”

(Samuel R. Delaney), “Out of All Them Bright Stars” (Nancy Kress), Arrive at Easterwine (R.A. Lafferty), or even

my own “Timothy Leary, Batu Khan, and the Palimpsest of Universal

Reality.”

Of course,

arresting titles need not be elaborate (although a review of Hugo and

Nebula nominees reveals something of a fashion for this in SF). The Maltese Falcon is short, descriptive, and carries a hint of the exotic. It inspired my own title, The January Dancer. Niven and Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer and Greg Bear’s The Forge of God

are effective for the same reason. John C. Wright would like a title

to be “brief, striking or memorable to the reader, and to tell the

reader immediately what genre the book is. If the title includes an odd

or invented word, or a combination of words not normally found

together, this is better still.”

A good way to arrest the attention is to evoke imagery. “I want

graphics,” writes Jack McDevitt. “I want a visual, connected with an

emotional impact, or at least an insight into where the narrative is

going.” He suggests joining a physical object with an abstraction. For example, his own Eternity Road (which is one of my own favorite titles) joins the physical Road with the abstraction of Eternity and “takes on the changes brought about by the passage of time.”

Because genre readers like to read genre, John Wright suggests SF titles include words like star or world or otherwise suggest SF and offers The Star Fox (Poul Anderson), Rocannon’s World (Ursula K. LeGuin), Forbidden Planet (“W.J. Stuart” (Philip MacDonald)) and World of Null-A (A.E. VanVogt) as examples. The last-named contains the mysterious, and therefore arresting neologism null-A. He also cites the hard-to-find Harry Potter and the Sky-Pirates of Callisto vs. the Second Foundation.

2. Suggestive. Now, if arresting the reader’s attention were

the only quality for a title, every story would be entitled "Secret Sex

Lives of Famous People” or perhaps Golden Bimbos of the Death Sun.

Michael Swanwick writes that the title “should suggest that something really interesting is happening in the story.”

The simplest way to do this is with a title that captures the essence of the story. Heinlein's Tunnel in the Sky is not only arresting (a tunnel in the sky?) but suggests what the story will be about. William Trevor’s mainstream story “The General’s Day” chronicles the

banal events of one day in the life of a retired British general (with a

devastating ending).

However, “suggestive” need not mean mere description. Suggestive means to hint, to adumbrate something about the story.

i) Not too revealing.

Ed Lerner cautions that the title should avoid revealing anything

critical in the story. Geoff Landis concurs: “Something evocative and

also fitting for the story, but doesn't give away key points of the

story.” The art of story-telling is to present events to the reader in an order that produces the best artistic effect. So Odysseus Comes Home Late would be a bad title, even though it is correctly descriptive. Never Mess with a Veteran's Wife is better, but only marginally less revealing.

ii) Metaphoric or symbolic. Edmund Hamilton's The Haunted

Stars concerns the discovery of an abandoned alien base on the Moon, and

the imagery of vanished peoples and long-ago deeds pervade the book.

John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider concerns a protagonist who “surfs the wave” of Future Shock. Juliette Wade tells us that her titles grow out of thematic ideas or important recurring concepts in the story, like the title of her novel, For Love, For Power.

Nancy Kress also admires titles that work on both a plot and a

thematic level, like LeGuin's "Nine Lives." Sara Umm Zaid entitled her

2001 Andalusia Prize story “Making Maklooba.” Maklooba is a

Palestinian dish in which the bowl is turned upside down on the tray

and removed. If the maklooba is good, the food retains the shape of

the bowl. The dish is used as a metaphor for a woman whose life has

been turned upside down and emptied by the death of her son and its

subsequent political exploitation. John Dunning used the title Two O’Clock, Eastern Wartime

for a tale of murder set in the days of live radio and World War II.

Kipling’s “The Gate of the Hundred Sorrows” is likewise suggestive

while also being descriptive – it is the name of an opium den where the

main story takes place.

iii) Atmosphere. The title might also be suggestive by

conjuring an atmosphere. For science fiction, that might be a title

that conveys a sense of “cosmic deeps of time.” For fantasy, one that

conveys a “haunting sense of melancholy.” In fact, Roger MacBride Allen

wrote The Depths of Time, which surely conveys that sense of cosmic deeps of time! The sequel The Ocean of Years succeeds by pairing ocean with years. Edmond Hamilton’s City at World’s End does a little of both, hinting at depths of time and a sense of melancholy.

3. Challenging. You can also catch the reader’s interest with a

title that challenges him. An odd word might be used – Null-A, Dirac

Sea, Feigenbaum Number, and so on. Ed Lerner suggests that the

relevance of the title might become evident only after the reader has

finished the story and reflects on it.

Juliette Wade likes titles that can have more than one meaning, such as

her own “Cold Words,” which is both literal and metaphorical. John

Dunning’s detective title The Bookman’s Wake seems to mean one

thing during the course of the story, but takes on another meaning at

the end. Patrick O’Brian’s naval novel The Surgeon’s Mate also

carries two meanings. Sara Umm Zaid’s “Village of Stones” refers not

only to the material construction of the dwellings, but to the

enthusiasm with which the villagers stone a young girl who has

dishonored her family. We might call these double-take titles.

But be careful. A title may be so challenging that the prospective

reader scratches his head in bewilderment and goes on to another book or

story. Long, obscure titles could tip over into a perceived

pretentiousness. Apparent metaphors could fail to deliver. James

Blish’s The Warriors of Day had a nice title, but it turned out

to be prosaic: actual warriors from a planet called Day. Double

meanings could be unintentional. “The Iron Shirts,” my alternate

history story for tor.com, was originally titled simply “Iron Shirts” until it

was pointed out that “iron” might be read as a verb!

G.K.Chesterton was fond of alliteration in

many of his Father Brown mysteries: “The Doom of the Darnaways,” “The

Flying Fish,” and so forth. Try saying aloud such titles as “The Last

Hurrah of the Golden Horde” (Norman Spinrad), “The Sorrow of Odin the

Goth” (Poul Anderson), The Stone That Never Came Down (John Brunner), Riders of the Purple Wage (Philip José Farmer). Each has a rhythm that makes it attractive.

But a short, punchy title can have its own charms: Warlord of Mars (Burroughs), Jumper (Steven Gould), Star Gate (Andre Norton).

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

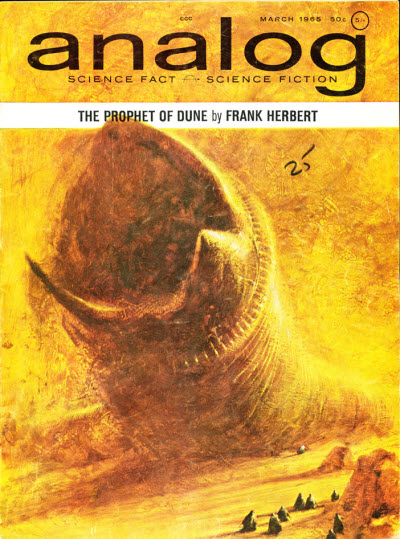

A good title may mask a bad story. Similarly, a good story may have a so-so title. Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen (H. Beam Piper) is a worse title than the one the original novelette bore: “Gunpowder God.” Even the blockbuster Dune,

whose title John Wright says “conjures up an image of a small hillock of

sand at the beach,” had better titles in magazine serial form; viz.,

“Dune World” and “The Prophet of Dune.” The First Shall be Last

The title may be the first thing the reader sees, but it might be the last thing the writer sees.

Some writers start with a title and write a story

from it. I tend to fall into this bucket. So does John Wright, who

says he has not only a notebook where he writes down story ideas, but a

file where he writes down interesting possibilities for titles. Jack

McDevitt likewise confesses, “I have a hard time writing the narrative

until I have a title in place” and Geoff Landis typically finds his

working title becoming the title of the finished story.

Other writers, however, don’t come up with a title until the story is

complete or near enough. For many, the final title is a struggle or,

in Michael Swanwick’s case, “a hideous struggle.” His working title

for the award-winning Stations of the Tide was… Science Fiction Novel, and it “came perilously close to being published as Sea-Change,

being saved from this fate on literally the last day the title could

have been changed.”

Nancy Kress seldom has even a working title while

she writes, and often struggles with the titles afterward. “I have no

good titles that I chose myself,” says Nancy Kress, “with a few

exceptions. Otherwise, I grab the sleeve of any one I can and say ‘Will

you read this and title it for me?’” Geoffrey Landis says, “I usually

struggle for a while and then give up and give it something obvious.”

Ed Lerner tells us, “I generally go through several titles before one

sticks.” For Harry Turtledove, it is “almost always a struggle” with

occasional exceptions. His original title for "The Pugnacious

Peacemaker" (a sequel to L. Sprague deCamp's “Wheels of If") was "Making

Peace with the Land of War,” which he thinks was perhaps too long and

obscure.

On the other hand, Juliette Wade says that while she has struggled once

or twice with titles, she usually doesn’t have that much trouble,

especially with her Allied Systems stories. For Bill Gleason, titles

“don’t come easily, but it hasn't really been a struggle either.”

Jack McDevitt swings both ways. He has occasionally spent an entire

year trying to come up with a title and still ended with one that was

unsatisfactory. “The Hercules Text was my first novel,” he

says. “The book, I’m happy to say, was considerably better than the

title, which made it sound like a school assignment.” But he had other

titles, like A Talent for War, before he had even the germ of a plot to go with it.

Where Do You Get Your Titles From?

Titles crawl out from under a variety of rocks, even when we have to

turn the rock over with a stick. Four sources are the four dimensions

of a story: theme, setting, characters, and plot.

1. Theme: The title can be a word or phrase that

captures the essential idea of the story. This is probably the most

popular category of titles. The idea may be described directly, as in

the mainstream book Room at the Top (John Braine) or by means of a double-meaning, as in The Bookman’s Wake (John Dunning) or a paradox, as in Casualties of Peace (Edna O’Brien). Examples in SF include: Thrice Upon a Time (James Hogan), Mission of Gravity (Hal Clement) or Dark as Day (Charles Sheffield).

2. Setting: A book can take its title from the milieu in which it takes place. This can be literal or metaphorical. Examples include: Ringworld (Niven). “The Gate of the Hundred Sorrows” (Kipling). Eternity Road (Jack McDevitt). Venus (Ben Bova). Red Mars (Kim Stanley Robinson). “Gibraltar Falls” (Poul Anderson). Or my own Eifelheim.

Because SF often involves strange milieus, and readers are attracted

to futuristic or alternate settings, this is a popular class of title.

4. Plot: A name or phrase that captures some peak

situation or occurrence within the story. Typical examples include

“The Madness of Private Ortheris” (Kipling), The Fall of the Towers

(Samuel R. Delany), and “The Green Hills of Earth” (Heinlein). The

last refers to a poem composed by the character Rhysling during the

story crisis. Mars Crossing (Landis) and “Nano Comes to Clifford Falls” (Nancy Kress) are summaries of their respective plots.

Poking the Muse

There are several ways of jogging the creative juices to emit a title from the brain-pan.

1. Simple description. A nanotech story of mine

was called “Werehouse” because that was where people went to be

illegally transformed into animals. Such titles often take the form

- Noun (The Syndic, C.M. Kornblunth)

- Adjective Noun, (The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett),

- Noun Noun (Dinosaur Beach, Keith Laumer),

- Noun of Noun, ("Flowers of Aulit Prison," Kress)

and so forth. For place-titles, try tossing prepositions like At, In, On, To, etc. while you ponder your story and you might come up with To the Tombaugh Station (Wilson Tucker), “On Greenhow Hill” (Kipling), In the Country of the Blind (yours truly).

2. A line from the story. Search the text of your

story for a line that seems to encapsulate the story. That was the

origin of “Places Where the Roads Don’t Go.”

It was also how Nancy Kress found titles for "Out of All Them Bright

Stars" and "The Price of Oranges," and R.A. Lafferty obtained “Camels

and Dromedaries, Clem.”

3. Famous (or not so famous) quotations. Make a

list of key words from each of the four categories mentioned above and

go to Bartlett’s to see if there’s a quotation that illuminates the

story. Shakespeare and the Bible have been overused, though there is a

good reason why people fish there for pithy quotes. But why not look

for the road less traveled and try Matthew Arnold, Algernon Swinburne

or Lewis Thomas? This was how I found “Where the Winds Are All

Asleep,” “Great, Sweet Mother,” and “The Common Goal of Nature.” I

also mined quotes for “Dawn, and Sunset, and the Colours of the Earth”

and “The Clapping Hands of God.” Harry Turtledove took “In the

Presence of Mine Enemies” from Psalms 23:5 – and “The Road Not Taken”

from Frost. Bill Gleason used Dylan Thomas.

Lawrence Block’s Small Town comes from a passage by John Gunther – and refers to New York City, which makes for an arresting contrast.

4. Pairings. BruteThink is a creative thinking

tactic that consists of finding two words that are individually

contrasting but which in combination capture the story. From the list

of key terms suggested by the four categories, look for pairs that

clash. Charles Sheffield’s Dark as Day, for example; or Nancy

Kress’ “Flowers of Aulit Prison.” Flowers + Prison? What’s that all

about? Another contrast, which Jack McDevitt has mentioned, is to join

a physical thing with an abstraction, as in his Infinity Beach, Nancy Kress’ Probability Moon, or Kipling’s “Dayspring Mishandled.”

5. Crossing categories. A good title might suggest

itself by pairing key words from different categories. For example,

an event and a place, as in Kipling’s “The Taking of Lungtungpen” or

Dashiell Hammett’s “The Gutting of Couffignal”; or a character and a

place, as in de Camp’s Conan of Cimmeria. Try each pairing and see what comes up: “The Character of Setting,” “Of Idea and Character,” and so on.

6. Random matches. Mozart used to roll a trio of

dice to suggest chord progressions. He would take the

randomly-generated chords and see if they inspired his creative

juices. If not, he would keep rolling until something came up. The

writer can do the same thing, taking words from the list of key words

purely at random and rubbing them against one another to see if any of

them strike sparks.

A Note on Series

Stories or novels in a series present an additional challenge. Each of John D.

MacDonald’s Travis McGee books has a color in the title; as does Kim

Stanley Robinson’s Martian trilogy. The Cliff Janeway novels of John

Dunning all have “booked” or “bookman” in the title. My own Firestar

series had the word “star” in each of the titles. Nancy Kress did the

same with her Sleepless books and her Probability series. Ed Lerner

and Larry Niven included the phrase "...of Worlds" in each book of their

Fleet of Worlds series.

But this is by no means a requirement. Neither Jack McDevitt’s

Priscilla Hutchins novels nor his Alex Benedict novels have such “marker”

titles. Neither do my own Spiral Arm books. Lawrence Block uses a

title pattern for his Burglar books (“The Burglar Who….”) but not for

his Matthew Scudder books. However, a title pattern is a choice that

you might keep in mind if you have a series.

Now that you have a title, get on with it! And don't be concerned if you wind up changing the title.

Contests

Our favorite titles. Okay,

dear readers, assuming there are any. Your assignment is to share book or

story titles that you found effective, memorable, or resonant,

regardless of the quality of the story itself. That is, titles that

lured you to buy the book or read the story, or which have stuck with

you afterward. What about the title enticed you? What made it work.

You don’t have to restrict yourself to SF titles, either.

Old wine in new bottles. Pick a book or story you liked, and suggest an alternate title for it. John Wright says he “would have changed I Will Fear No Evil into "Brain-Swapping Lust Ghost of Venus or something.” And Foundation he would have called, Mind-Masters of the Dying Galactic Empire. What titles can you come up with? You can

a) suggest serious alternatives to titles you thought didn’t quite make it, or

b) try to out-gonzo Mr. Wright.

The prize… Well, there ain’t no prize. We don’t need no stinking prizes. It’s an honor just to participate.

Coming Soon: Another Fine Mess

Each of these triggers -- the farmer's excavation, the abusive father, the lightning bolt, the Pierson's Puppeteer, et al. -- is external to the character

of the Main Actor: to Max and April, Davy, Martin, Louis, and Donovan

buigh.

Each of these triggers -- the farmer's excavation, the abusive father, the lightning bolt, the Pierson's Puppeteer, et al. -- is external to the character

of the Main Actor: to Max and April, Davy, Martin, Louis, and Donovan

buigh.

.jpg/330px-The_Maltese_Falcon_(1st_ed_cover).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)