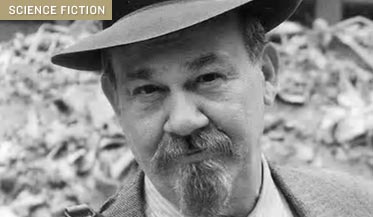

The Despair of Thomas Disch

Thomas M. Disch, the late SF writer (poet/critic/...), once told Jody Bottum that part of the reason he quit writing science fiction was that, to deepen it into real art, "I would have to be like Gene Wolfe and return to the Catholicism that I barely got away from when I was young -- and I can't do that, of course."

That "of course" is heartbreaking. Bottum commented that Disch "never escaped his escape from Catholicism." And there is something to that. It's a sort of intaglio, defining oneself by what one is not; and one cannot help but be reminded of holes and gaps left unfilled. His suicide was a tragedy and a loss to literature in general and SF in particular. He was once called "the most respected ... and least read of all modern first-rank SF writers." He ought not have been.

|

| The Taking of Christ, 1602, oil on canvas, 53 X 67 in., Michelangelo da Caravaggio, |

|

| Niña con lazo y flor, mix media on canvas, 73x54 cm, José Manuel Merello |

Impersonating the Person

In the world of Late Antiquity, a series of Church Councils hammered out our modern notion of a "person." Originally meaning only the mask worn by a Greek actor, the term was applied to the hypostases of the Godhead, and came ultimately to apply to individual human beings. Each of us was conceived not simply as a component in a polis, but as a separate individual with an inner life and a sense of synderesis, and from this all Western law draws its substance.

Psychology is, by definition, the science (logos) of the soul (psyche), but modern psychology denies the soul and so has declared itself to be without a subject matter. Schools of psychology war amongst one another over basic questions of what they are actually trying to study in a manner that has never much troubled physicists or chemists or, on most occasions, biologists. Two basic stances have emerged from the wreckage of Cartesian dualism:

- Idealism limits itself to consciousness "and its immediate data."

- Materialism limits itself to behavior, and rules out any reference to consciousness.

Materialists conclude that consciousness, will, and even self are "illusions" (suffered by whom?) principally because their chosen methodology cannot "see" them.(*) It would make psychology a subset of biology. Idealists otoh would make a science of psychology (based on controlled observation) incoherent. Brennan writes:

(*) As Heisenberg wrote: "What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.""Having lost its soul, its mind, and its consciousness, in that order, psychology is now in danger of losing its scientific standing."

|

| A synolon: sphere+rubber if it were alive |

TOF's Perceptive Reader will note the humorous dichotomy of the two schools and the irony of the more modern reaction of the personalists, psychodiagnosticians, and factor psychologists mentioned by Brennan, who have fallen back on an older "synolistic" view of man. The word (which evidently gave rise to the modern "wholistic") comes from the synolon, the soul+body composite to which an earlier psychology attributed the nature of man.

Since a synolon is both psyche and soma, a synolistic approach incorporates both idealist and materialist insights and places them in ratio to each other. Surely, this is a richer approach than either partial psychology of the Late Modern Age, and it is one that accounts more fully for the person.

Fiction and the Person

One of the duties of the novelist -- some might say his or her primary duty -- is to fabricate artificial persons: the characters of the novel. If our writing is informed by a fragmented modern psychology, these characters may appear to the Reader much as the Merello painting above: a sketchy figure with a doll's face. You look in its eyes and there's nobody home.

Perhaps this is what Disch meant. He is no longer available for comment. But Catholic teaching has always envisioned the human being as a synolon, with all the complexity that implies, and neither as a Cartesian ghost in the machine nor as a meat puppet. Meat puppets may sound all edgy and transgressive at the Kool Kids table -- take that, bourgeoisie! -- but they make for damned poor characters in fiction.

Why? Because, like the Merello figure above, they don't look much like people we've encountered in our own lives. (Even if sometimes they capture one aspect or another.) And that ought to tell us something about deepening fiction into art.

Of course, to deepen fiction into art may not require a return to Catholicism, although that may help a great deal. Aristotle, after all, was not. Orthodoxy has much the same approach to the psyche, and so for that matter has Judaism or even the good old-fashioned humanism (not the new-fashioned humanism of the poser). Old Humanism was, after all, all about humans, and what matters is the synolistic understanding of that human. This is sometimes available by introspection or by intuition (save for those whose psychology does not allow such concepts) but also by analysis. So from time to time over the next few months TOF proposes to mumble here on the human soul and what it means for fiction.

Suggested Reading

Aristotle of Stagira. De anima.

Brennan, Robert. Thomistic Psychology (Macmillan, 1941)

Impressionism was, arguably, the artistic form of materialism—the "impressions" being, basically, material properties divorced from all questions as to "identity", material and efficient causes without formal or final ones. I seem to recall that that was explicitly spelled out when they talked about the "theory" of their school.

ReplyDeleteI have read psychologists flatly denying free will because you can't have a science of something with free will.

ReplyDeleteI should probably admit that I wrote that piece for the Weekly Standard shortly after Tom's death, and I was very, very angry with him in my grief. I've mellowed a little, in the passing years, and pray for his soul in purgatory.

ReplyDeleteThat said, I think that Tom may have meant less something about the characters in his fiction and more about the metaphysically rich universe, the world of living and cosmically charged symbols, that is one of the things that makes Wolfe so fascinating—and one of the things Tom missed in his own sci-fi: He knew he could draw genuine characters, and he also maybe understood that he couldn't make them matter in a cosmic sense.

Only a guess, of course, but the line did come from him in the middle of a conversation we were having about Wolfe (over an epically awful lunch in Union Square one day, as it happens). Dana has some great Tom stories, too, if you need more.

Jody

Thank you for the comment. I was not willing to go quite so far, since I was speculating at a couple of removes from the comment (and my intent was specifically to lead into a set on Thomistic psychology). Perhaps this is meat for a later post.

DeleteFWIW, I think a certain magazine has suffered somewhat since you left it. You may find my story "Hopeful Monsters" in Captive Dreams interesting, since it is based on an essay written by Fr. Neuhaus.

http://www.amazon.com/Captive-Dreams-Michael-Flynn/dp/1612420591

Hah. I'll certainly read the story. For your amusement, here's a short story I wrote last fall for Standpoint magazine in London, a piece of fiction also based on something RJN once said, in a conversation we had about coming to faith: http://standpointmag.co.uk/text-october-13-folie-a-dieu-joseph-bottum

DeleteAs far as your use of the anecdote about Tom Disch goes, I take your point that you were hunting psychological game. I will say, though, that a cosmically rich, metaphysically thick universe is not unrelated to the rich, thick psyche you want to see in fiction.

> Materialists conclude that consciousness, will, and even self are "illusions" (suffered by whom?)

ReplyDeleteHa! That's a wonderfully crisp distillation of your (our) point.

Well done.

Homework and/or Sneaky Tricks! heh heh heh. Looking forward to the series.

ReplyDeleteNot sure if you'll see this, Mr. Flynn, but I have discovered a tidbit about Albertus Magnus which you might find illuminating, particularly for future posts that mention/treat of that great man.

ReplyDeleteIn several of your posts, according to my memory, you have quoted Albert as saying this in his De vegetabilibus:

"In studying nature we have not to inquire how God the Creator may, as He freely wills, use His creatures to work miracles and thereby show forth His power; we have rather to inquire what Nature with its immanent causes can naturally bring to pass."

The problem is, I've never been able to find a reference to the specific part of that treatise where this quote may be found. However, I discovered in the old Catholic Encyclopedia an English quote from Albert very much the same in content, but the reference is to his De coelo et mundo, I.iv.10. I checked the Borgnet edition (vol. 4) of Albert's Opera Omnia and discovered that this reference is indeed correct. From p. 120 (no. 140), where he speaks of the opinion of Plato on the indissolubility of the heavens:

"Si quis autem ad omnia haec respondere velit secundum Platonem, et dicat omnia haec coelum et stellas natura quidem esse dissolubiles, eo quod sunt generatae: sed voluntate opificis esse indissolubiles, eo quod hoc quod bona ratione compositum est, non decet sapientem opificem dissolvere, quemadmodum dicitur in Timaeo. Dicemus hoc dictum non esse naturale omnino: quoniam sicut habitum est in Physicis, naturalia sunt agentia quorum actus sunt in passivis, et naturaliter patiuntur quaecumque talium actuum sunt susceptibilia: et ideo omne factum in natura, oportet quod habeat in eadem natura suum faciens: et ideo possibile et impossibile oportebit referre ad materiam rei factae et ad causam separatam et extrinsicam. Quod igitur corruptibile est de natura, hoc est simpliciter corruptibile, et habet causam in natura quae agit suam corruptionem: et si non habet talem, ipsum est incorruptibile, quia aliter omnia possent dici incorruptibilia, quia sunt incorruptibilia si Deus vult: et ideo supra diximus, quod naturalia non sunt a casu, nec a voluntate, sed a causa agente et terminante ea: nec nos in naturalibus habemus inquirere qualiter Deus opifex secundum suam liberam voluntatem in creatis ab ipso utatur ad miraculum quo declaret potentiam suam, sed potius quid in rebus naturalibus secundum causas naturae insitas naturaliter fieri possit."

Anyway, I thought you might like to know this, in case you wanted a more definite reference when using that quote of Albert's. (The English translation you often quote isn't exactly literal--my preference in things like this--but it captures the sense of the Latin well enough for one to get the gist of what he's saying. The context does help, though.)

Whoops, I should say that this is taken from pages 119-120 of vol. 4 of the Borgnet edition, not just page 120.

DeleteGratia ago tibi.

DeleteGratiaS, dear Mr. Flynn!

DeletePerfect comment, it reminds me of what once wrote Flannery O'Connor about the necessity to be an Artist if you are Catholic in a saecular world (and not the other way around)

ReplyDelete