|

| You are here, or not |

...and so on into the background of the IRT, BMT, and how the IND differed from the others... etc. etc. Dig it.

Some famous infodumps include:

- The "cetology" chapters in Moby Dick.

- The "Catalog of Ships" in the Iliad.

- The "begats" in Genesis

- Arguably, the entirety of Lord of the Rings

|

| Fun on the funicular. Budapest, in case you're wondering |

On the Other Hand, one may as easily imagine a story which grows inexplicable because one lacks infordumpishly material. Some modern editions of Kipling have resorted to footnotes to dump info regarding topical references in the story that are no longer au courant among Readers. When Agatha Christie writes that Hercule Poirot rides the funicular up the side of an Alpine mountain, Late Modern readers outside of Pittsburgh, Budapest, and other select locales may justly wonder WTF is a funicular? But Christie does not explain. Still less does she explain how they work. She just assumes her readers will know. Similarly, the author of a story set in San Francisco needn't explain how cable cars work -- unless the story involves the mechanics of the system in some way, say a terrorist plot to cut the cables and send the cars careening down the steep hills.

So the Writer must strike a Happy Medium. This does not mean punching merry Madame Zarko in the nose, no matter what she sees in her crystal ball. Such a strategy is to be avoided at all costs. However, like Little Bear's porridge, the information must be neither too much nor too little.

So much depends on

- What info is dumped

- How much is dumped

- When and how it is dumped.

The Happy Medium

Info dumps usually result when the Writer has done a lot of research and wants the Reader to know it. (Or, more kindly, wants to share his fascination and enthusiasm.) Resist this. Not the fascination and enthusiasm, the going on about it. The Writer, so it is said, "must suffer for his art," but there is no reason why the Reader must do the same. Not for nothing do we complain: "That's too much sharing."The trick is to figure what information the reader needs either to:

- understand the story or

- experience a fully-textured world ("atmosphere")

| White Rooms lack the information to become real |

For the most part -- and even Famous Fantasy Writers with middle initials of RR sometimes nod -- these details make their utterly fantastic realms seem "fleshed out" and "lived in." For the opposite of the Infodump is the deadly White Room.

The characters approach a ruined castle, whose very stone appears melted. The reader will naturally want to know WTF? The White Room is text that is insufficiently infodumped. Too few details or background are provided. There is no sense that the world extends any further than the edges of the page, or that life began before the story opened, and will continue after it ends.But if as they approach the aforesaid castle one of the characters mentions to another that the castle had been melted by dragons from the air when the Targaryens were establishing their rule, centuries ago. As long as he doesn't run his mouth, that tidbit makes the castle more real -- and hints that dragons are way cool if you can use them against your enemies. Too bad they're all gone now. Or good thing, depending on which side of the castle walls you're on.

|

| John Dunning |

An example of thumb-description: In TOF's The Wreck of "The River of Stars" the engineer and others speak of the fusion thrusters in off-hand references to "the cages" in passages like this:

Miko threw the switches and locked them out,

one by one. The engineer [Ram] was terrified of outside work. He tried

to keep it secret, but Miko could tell. A cold start would require

recalibration of the flicker. Someone must physically adjust the

focusing rings after each test burst. It was dangerous work, normally

done in the Yards. Get the rhythm wrong -- miss a beat -- and a

nanopulse of fusion would be more than flesh and bone could bear. The

situation must be serious indeed if Ram was willing to accept that risk

while under way and with a high velocity.

There is no need to explain what a flicker is and why it must be calibrated after a cold start, nor what focusing rings are. Simply to speak knowingly about them reassures the reader that the narrator knows what he's talking about and can be trusted. No need for a detailed infodump on the structure and workings of a Farnsworth fusion cage.

Virtus in media stet, the Romans said. "Strength stands in the middle." Background information and descriptive detail are best served when they avoid the two extremes of the Infodump and the White Room.

The great Master of this craft was Rudyard Kipling, whose Knowing Voice was echoed by Robert A. Heinlein in the SF field. Here is Kipling in Kim, where Lurgan tells Kim about doctoring sick jewels. Doctoring sick gemstones? WTF?

"Oh, they are quite well, those stones. It will not hurt them to take the sun. Besides, they are cheap. But with sick stones it is very different." He piled Kim's plate anew. "'There is no one but me can doctor a sick pearl and re-blue turquoises. I grant you opals -- any fool can cure an opal -- but for a sick pearl there is only me. Suppose I were to die! Then there would be no one... Oh no! You cannot do anything with jewels. It will be quite enough if you understand a little about the turquoise -- some day."There is no need for a lengthy disquisition on what jewel-doctoring is or how it is carried out. We are satisfied that Lurgan knows -- and Kipling knows, even if he made it up from whole cloth. The comment "any fool can cure an opal" is a master touch. In a few words, Kipling suggests a depth of knowledge about the profession, degrees of difficulty, and so on.

How to Dump

There are several ways to dump the info needed for the reader's understanding or to paint your white room:- The Dump Direct

- Lipstick on the Pig

- The Lecture

- The Visitor

- The Debate

- The Dice-and-Slice

Eugenie Satterwaithe had been plying the solar system in concentric ripples ever since she had first jumped into that vast, dark ocean. She had flown in the beginning as a ballistic pilot: a young woman, lightning-witted, riding a fiery arc between the antipodes of Earth. ....

and so on, describing her career up to the time of the story. To dribble this information out in passing conversations or comments would bloat the narrative. Early SF often did this badly. There are several instances in Heinlein's Betond This Horizon, in which he stops the story cold to describe the computerized socialist economy of his utopia. Later, he learned better.

|

| Kipling's ads for planes and dirigibles |

- At the end of his 1905 short story "With the Night Mail: a Story of 2000 AD" (which portrays a future in which mail is delivered by aircraft!) Kipling added a couple of pages of fictional advertisments for aeroplane equipment (including catapaults) and their prices. Remember, the Wright Brothers had

not flown yet.flown only two years before. - Marc Stiegler's 1988 novel, David's Sling, was the first novel written on what were then called "hypercards" intended to be read on a computer and "navigated" via "links." It could be read from the POV of any of four characters. Chapters were written from the POV of each one present and the Reader would come to that chapter with no more knowledge than his chosen POV character had. The novel also included drawings and schematics of the various hardware being developed, background on characters, a PERT diagram of the Sling Project, and so on. Each could be "accessed" at appropriate points in the hypertext.

2. Lipstick on the Pig. Sometimes the infordump can be made entertaining in its own right, through grace of writing. A teaspoon of sugar can help the medicine go down. Even the dread cetology chapter in Moby Dick is worth a look. The entire book is modeled after ancient epic poems, which were famously digressive. One commenter thinks the chapter is hilarious:

'The narrator divides the whales into classification categories, which he calls "books" and "chapters." The three "books" of whales are the "folio whale," the "octavo whale," and the "duodecimo whale." This is another book joke, because folio, octavo, and duodecimo are three common nineteenth-century sizes of books."IOW "whales are being treated as novels in a novel about a whale." ROFLOL

(It's not even an infodump, properly speaking, since much of the "info" is bogus!)

So one way of making the infodump palatable is to make it funny or interesting in its own right.

You Don't Know Jack.

Another way to dump info is to have one character tell another the info the reader needs to know. As you know, Bob, never have a character tell another something the other already knows.3. The Lecture. This takes the dump out of the mouth of the narrator and puts it in the mouth of a character. In this case, the character is instructing a class, giving a speech, or some other similar thing, and his audience does not know the information and, like the reader, must be told. Heinlein commits this multiple times in the novel Starship Troopers (not to be confused with the movie that used the title) where he tries to explain the origins of the political system through the lips of classroom instructors and students who have never given thought to the matter. In another famous chapter, the first person narrator breaks into the story, apologizes for interrupting the narrative (!) and explains how the power suits work. He says he is doing this so the reader (He has been told to keep a diary) understands the importance of the suits to the trooper and also because it was the proximate cause of his getting an administrative punishment.

4. The Visitor. When the info is dumped mano-a-mano, as it were, the one on the receiving end should be an outsider or newbie so the first character is justified in telling him things. Heinlein (1940) did this in "The Roads Must Roll" by having the main character, Gaines, take a visiting Aussie official on a tour in which he explains how the giant conveyor belts work to carry pedestrians from city to city -- and also how dependent the country is on these rolling roads continuing to operate under the control of dedicated operators. Among Heinlein's papers are detailed drawings of the roadway machinery and maps of the roadways. But none of that made it into the story.

In addition to visitors from Australia, Heinlein used a visitor from the past in Beyond This Horizon. Visitors from outer space may also need things explained; as would Earthlings visiting other planets.

This tactic has the benefit of working the information into a conversation. TOF once wrote a lecture on the coming Ice Age into a panel discussion at a science fiction con in Fallen Angels, but Niven and Pournelle, his collaborators, broke this up into snatches of conversation during a rousing party.

5. The Debate. Two or more characters argue over something. This tactic is better than the Lecture because there is at least some conflict going on. TOFused this in his Irish Pub stories: "From the Corner of the Eye," "3rd Corinthians," "Where the Winds Are All Asleep," et al. In the last-named story, the argument in the bar begins as follows:

“And what conference was that?” Kelly asked.This allows Jeanne Price, the biologist, to explain abiogenesis and the monogenic problem (did life originate once or several times in the early seas?), to answer questions, dispel misconceptions, declare that she doesn't want to talk about it any more, fall morosely silent,and (eventually) tell the others in the bar the story of what had happened to her.

“Approaches to Abiogenesis and the Monogenic Problem,” she answered – though to no great enlightenment on anyone’s part. Seeing our perplexity, she added, “Abiogenesis is the origin of life from non-living matter.”

A crafty gleam came into Doc’s eye, and I shot one anxious glance toward the pool room before whispering, “No! Don’t say it!”

But it was no use. “You mean it has to do with e-vo-lution?” the Doc announced; and no sooner had the words slipped the leash of his tongue than Danny Mulloney burst forth from the back room, cue in hand, seeking infidels to smite.

You see, Danny had forsaken Holy Mother Church a few years back for one of those sects that worship a text rather than a God, and “evil-ution” was the pea under his personal mattress. Doc and he had danced this particular jig more than once in the past. Like the old war horse, “he sayeth among the trumpets Aha! and smelleth the battle afar off.”

|

| British cover |

“Where were you when the Armleder went about the Rhineland hanging the rich men and burning their houses?”The last phrase is all that is needed at that point in the narrative regarding the Armleder. There is no need to stop the narration and infodump all about the peasant revolt. More details will come out later, and we learn why it matters so much to Dietrich. We might call this the Infodribble rather than Infodump. Instead of a great undigested mass of data, it is served up in bite-sized pieces.

A master of this tactic is Jack McDevitt, many of whose books consist primarily of progressive discovery of the info dump. His first Alex Benedict story, A Talent for War, is worthy of study. The reader learns about the course of the Resistance against the alien Ashiyyur, the various battles, the brilliant Fabian campaign of Christopher Sim, etc. in backstory, told in small pieces as Benedict tries to put together a picture of what happened 200 years earlier. (The backstory is essentially the quarrelsome Greek city states vs. the Persian Empire.) It is worth study by writers for this reason alone.

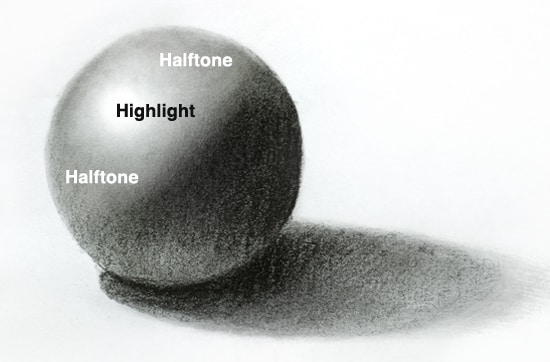

So, perhaps the most effective method of giving the Reader the necessary information to understand the story is to chop it up and parcel it out in bits and pieces. Additional information that adds "color" is best applied sparingly, like the shadows added to plane figures to make them seem three dimensional.

SF readers tend to be tolerant of puzzles, trusting the author to eventually explain or at least finesse it. Thus in The January Dancer TOF did not try to explain how the "alfven engines" could "grab the fabric of space" but simply declared that they did so.

Infodumps are most needed where the reader comes to a text with contrary expectations rather than with no expectations. For example, Part I of The Shipwrecks of Time, currently in progress, starts in Milwaukee in 1965. This was a time when there were no four-function hand calculators, let alone an internet. Phones were pretty much all land-line, still nearly all rotary -- and leased from Ma Bell. Women were routinely called "girls" and you were considered legally a child until you were 21, not 18. There was no Miranda warning and the "third degree" was common police practice. There were a couple of weather satellites taking snapshots, but weather was still something that took everyone by surprise. There was Crawdaddy, but no Rolling Stone magazine. "Male chauvinist" had not been coined; and so on.

In short, the past is a different country, but many modern readers will be coming to the book from the county of 2015 and may not realize what and how much was different. They might wonder "Why doesn't Frank use his cell phone?" (Few people will hold a conversation about things that don't exist. Gosh, thought Frank, I sure wish I had a cell phone, but they haven't been invented yet.) So TOF is trying to parcel out these tidbits here and there throughout the narrative: chit-chat at parties, breaking news on TV, and so on. In the following draft, set in the Institute office, Stu is the mailman taking shelter from a downpour, and Nelson is a research assistant with an enthusiasm for science fiction. He does plausibly talk about things that haven't been invented yet.

Carole had gone to the window. “It’s pouring,” she said unnecessarily.Various characters have different interests, so the feminist learns about the term "male chauvinist" when it is introduced. Another character grouses how contraception is only legal for married couples. A third thinks Miranda is going to ruin police work. A fourth when he arrives at work on his first day notes in passing that one of the typewriters on the desks is the new kind with "type-balls."

“So much for weather forecasts,” said Frank.

“Do you think it has anything to do with Hurricane Inez?” Carole asked.

“Don’t see how. She’s all the way down around Yucatan somewhere.”

“Weather satellites will change everything,” Nelson predicted. “They launched another one just a couple days ago, so there are two of them up there now, plus three of the old TIROS types. They send down wide angle and telephoto photographs of the cloud cover.”

“That a fact?” said Stu. “Does it help me stay dry this afternoon?”

Nelson flushed, but Stu laughed. “Don’t worry, kid. I grew up watching Mickey Mouse Club, so I know all about Tomorrowland – and I agree. It’d be great if hurricanes and storms didn’t catch us so much by surprise. Hey, remember the Telstar broadcast?

All of this is for atmosphere, and so cannot be allowed to take over center stage. But it is the backdrop against which the story is played out. So....

Dump all the info you want in first draft; then cut what you don't need.

I like the term "Infodribble" --I'm stealing it immediately for my students. But I offer in exchange the metaphor of one of our guest speakers, who said an Infodump was an all-crushing boulder, while the occasional nugget worked a lot better and preserved momentum. Drop nuggets, he said, don't roll a boulder!

ReplyDeleteMeanwhile, in the exotic country of Iowa, I'm developing a number of colorful metaphors in the process of correcting proofs. Somehow, strangely, it never comes up when authors discuss publication....

Another way to improve an infodump, as long as it is not too long, is to have it do double-duty revealing the "colorfulness" of the character relating the info by how he explains things, the mannerisms he's prone to, the excitement and love of the topic he displays, etc. However, this is no excuse to introduce such a character, or change an existing one, just to improve the infodump.

ReplyDeleteIn my case, how much I loved the ringing prose I used in a cherished infodump was almost always inversely proportional to the actual need to keep it.

There have been too few stories from your pen in recent years.

Delete1905 was two years after the Wright brothers first flew.

ReplyDeleteDang. Why did I have 1908 stuck in my mind??

Delete1908 was when they began to publicize their invention.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteSo, I really need to read "The Wreck of the River of Stars", just because that title is amazing.

ReplyDeleteIt's a terrific book.

DeleteDunning's "thumb and hand" principle is one I hadn't heard. Factual and fun treatise on a subject we all struggle with. This one is going to my article archive on craft. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteVery helpful, thanks.

ReplyDeleteOn the topic of the "Catalog of Ships" in the Iliad, we just were reading that out loud (son #2 is heading off to Thomas Aquinas College in a month, so we thought we'd all read the Iliad aloud). I thought it was less an info dump as a way to suck the listeners in, as I'd imagined that, for the early audiences at least, all those lands and peoples were familiar from their own histories. It would be cool to hear the legends of one's homeland and neighbors confirmed and expanded on. Only later, maybe, it would become tedious.

I always admired the way Ralph Ellison handled his infodumping in INVISIBLE MAN. Indirect and unobtrusive, but always clear. For example, instead of writing that a man was white, he would write that he was blond.

ReplyDeleteThe opening of the second chapter of that novel--I think it was the second chapter, anyway--where he sets the scene at the college, he makes it interesting purely through the force of his language and the motifs and symbols he incorporates. Call it the infodump-as-poem strategy. Not sure how applicable it is to genre fiction, but I like it.

I despise #4, The Visitor, as a method of infodump. It's wildly overused in fantasy etc. I think that's one of the reasons I enjoyed your writing as soon as I got into it. I started with Eifelheim and if ever there was a time for Visitor, that was it...and you went the other way. Much appreciated.

ReplyDeleteRob

Incredibly informative, this is great!

ReplyDeleteIt *is* a different genre, and thus has different goals, but what do you think about the digressions of Herodotus in _The Histories_? The sort of "before I speak about this battle, let me tell you about the culture and myths of the peoples who made up the opposing parties. Then let me tell you about the country it took place in, and the geography of its cities! And then...!" style?

It's the sort of thing the reader expects and wants in a history. Even in a fiction, it is tolerable in small doses. In Up Jim River, each planet visited by the harper and the scarred man gets a small background introduction.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete