Continued from Part V: The Great Cyrillic Flame War

AD 414/416. RUMORS FLY IN THE NAKED CITY. Why is Orestes so obstinate? Why will he not make kissy-face with Cyril? My wife's second cousin's brother says that Hypatia is the obstacle! Her counsel keeps the prefect at odds with the patriarch, and therefore perpetuates unrest in the City. Somebody oughta do something about that dame.

AD 414/416. RUMORS FLY IN THE NAKED CITY. Why is Orestes so obstinate? Why will he not make kissy-face with Cyril? My wife's second cousin's brother says that Hypatia is the obstacle! Her counsel keeps the prefect at odds with the patriarch, and therefore perpetuates unrest in the City. Somebody oughta do something about that dame.

An

account written two centuries later states that she was also rumored to

be a witch and magician, but neither Socrates nor Damascius say this. Now her father had practiced magic, but there is no evidence that she herself did so. OTOH, she did teach astrology and divination as means of learning God’s will. To the proletarians In the Lower City, the distinction may not have been clear.

Maria

Dzielska believes Cyril fomented the rumors, but this is one of those

things that depend on an assessment of Cyril’s character, not on

anything in the surviving records. He was certainly ambitious and seems capable of planting rumors; but OTOH he doesn’t seem that subtle, either. Drumming up a crowd of the 99% for a Direct Action seems more his style. For that matter, the rumors may even have been true. She may very well have been counseling Orestes to keep Cyril at arm’s length. Damascius writes:

Thus it happened one day that Cyril, bishop of the other party¹, was passing by Hypatia's house, and he saw a great crowd of people and horses in front of her door. Some were arriving, some departing, and others standing around. When

he asked why there was a crowd there and what all the fuss was about,

he was told by her followers that it was the house of Hypatia the

philosopher and she was about to greet them. When

Cyril learned this he was so struck with envy that he immediately began

plotting her murder and the most heinous form of murder at that. (Damascius’ Life of Isidore, as preserved in the Byzantine encyclopedia known as the Suda)

The

story is slightly improbable, in that Cyril could not possibly have

been unaware of who Hypatia was prior to this supposed incident. She had been important in Alexandrian life already when uncle Theophilus had still been patriarch. But Damascius was writing two generations later.

Note

1. other party. One translator interpolates “[i.e., the Christians]” but this is not in the text. The two parties are the pro-Cyril party and the pro-Timothy party (which has become the pro-Orestes party). So the passage means that Hypatia was aligned with Orestes, and Cyril was the opposition. Both parties are composed primarily of Christians. Hypatia belongs to the upper-class party – call her a country-club Republican – and Cyril to the lower-class party – call him a populist Democrat. The basic wrangle is over whether the bishops of the Empire are to be subordinate to the governors or whether they have administrative powers of their own. The same hassles are underway in Antioch and the other cities. (In the West, the imperial governors are disappearing and barbarian warlords are taking their place. The Pope of Rome will become by default the go-to guy for any sort of universal decision.)

1. other party. One translator interpolates “[i.e., the Christians]” but this is not in the text. The two parties are the pro-Cyril party and the pro-Timothy party (which has become the pro-Orestes party). So the passage means that Hypatia was aligned with Orestes, and Cyril was the opposition. Both parties are composed primarily of Christians. Hypatia belongs to the upper-class party – call her a country-club Republican – and Cyril to the lower-class party – call him a populist Democrat. The basic wrangle is over whether the bishops of the Empire are to be subordinate to the governors or whether they have administrative powers of their own. The same hassles are underway in Antioch and the other cities. (In the West, the imperial governors are disappearing and barbarian warlords are taking their place. The Pope of Rome will become by default the go-to guy for any sort of universal decision.)

Cyril’s jealousy was not pegged to her philosophical or astronomical attainments, as some claim. Damascius cites jealousy over the size of her morning clientele. He was likely frightened by the size of Hypatia’s faction. Hypatia, now a matronly 60 or 61, has considerable throw weight of metal. Among her former students:

- Heraclianus' brother Cyrus is a high official in Constantinople.

- Heysichius is duke and corrector of Libya, as well as a bishop

- Euoptius is bishop of Ptolemaeus,

- Olympius is wealthy landowner in Syria and a friend of the military governor of Egypt,

- Synesius’ friend Aurelian is the new praetorian prefect of the East.

Hypatia is in tight with most of the ruling class of Alexandria. Orestes

is backed by the Christian faction that had supported Timothy the

deacon, the Christians who had rescued him from the Nitrian monks. Orestes is the Christian governor of a Christian state, backed by a Christian emperor.

Cyril has friends among the poor plus a few supporters in the Upper City. He also has the parabolani. These were originally charged with the duty to gather up the sick and

homeless and bring them to the new-fangled “hospitals” that the

Byzantine Christians had invented. Cyril is thought to have converted the to his personal Brute Squad. But Cyril's supporters have little influence in the lifestyles of the rich and famous. In the power struggle with Orestes, Cyril sees himself losing.

The Murder of Hypatia.

416. Hypatia is about 60. The only surviving contemporary account of the murder is by Socrates Scholasticus, the same who also told us of the Deconstruction of the Serapeum, the Massacre of St. Alexander’s and the Attack on Orestes by the Nitrian monks. Scholasticus

was taught by two of the pagan rhetors who had led the occupation of

the Serapeum. He was critical of the patriarchs of Antioch, Rome, and Alexandria for suppressing the Novatians. This may have colored his attitude toward Cyril, who closed the Novatian parishes in Alexandria, but his account of Hypatia is generally considered reliable. Here it is, verbatim:

|

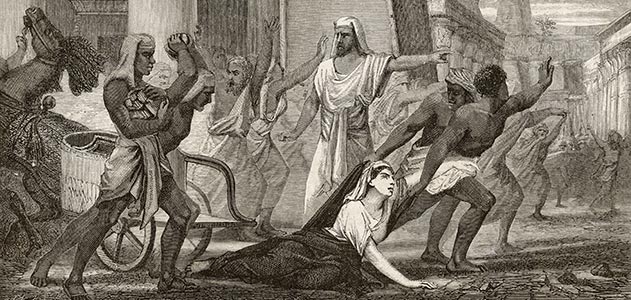

| The world has not lacked for fanciful renditions of the affair. Here, the lily-white Hypatia is dragged by swarthy proles The racial subtext is not hard to discern. |

Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For

as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously

reported among the Christian populace, that it was she who prevented

Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some

of them therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal, whose

ringleader was a reader named Peter, waylaid her returning home, and

dragging her from her carriage, they took her to the church called

Cæsareum², where they completely stripped her, and then murdered her with

tiles.³ After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs to a place called Cinaron¹, and there burnt them. This affair brought not the least opprobrium, not only upon Cyril, but also upon the whole Alexandrian church. And

surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the

allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort. This

happened in the month of March during Lent, in the fourth year of

Cyril's episcopate, under the tenth consulate of Honorius, and the sixth

of Theodosius.

Notes:

1. scientia. It would not be correct to translate the Greek as "science" since the modern category of natural science is not what was meant by the term. In the context of the 4th century, “attainments” in philosophy and science does not mean “discovering new things,” but “achieving great renown.” 2. The Cæsareum was a former pagan temple, once dedicated to the Divine Cæsar (Near the harbor: See the map of Alexandria in the Intro.)

3. Tiles. Lit. "oyster shells." This is interpreted by some as saying Hypatia was flayed, with her skin scraped off by shells. Of course, a flensing knife would be more efficient for this, and it is simply another lurid sado-masochistic 19th century fantasy. "Oyster shells" was simply a colloquialism for the curved roofing tiles. It could also be read as “broken pottery”. It is easy to make broken pottery out of roofing tiles.

1. Cinaron. The location is unknown, but likely nearby. Others killed by Alexandrian mobs had their ashes scattered into the sea, so perhaps it is near the shore.

One other contemporary source was an Ecclesiastical History by Philostorgius of Cappadocia. The full text is lost and we have only an epitome -- that is, a brief outline of the chapter contents -- prepared by the Orthodox patriarch Photius in the 9th century, four hundred years later. According to Photius:

Theodosius the Younger

One of the Bug-Eyed EmperorsPhilostorgius says, that Hypatia, the daughter of Theon, was so well educated in mathematics by her father, that she far surpassed her teacher, and especially in astronomy, and taught many others the mathematical sciences. The impious writer asserts that, during the reign of Theodosius the younger, she was torn in pieces by the Homoousian party. (Photius. Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, Book VIII, ch. 9)

The "Homoousian party" (Latin: "Consubstantial party") means what we would call the Orthodox Church. Philostorgius was an extreme Arian and therefore hostile to Cyril (which is why Photius calls him "impious"). He ascribes the blame to the Orthodox party in general. No details survive. Philostorgius (via Photius) describes Hypatia merely as a mathematics teacher, not a Neoplatonic philosopher, and gives no details aside from that she was "torn to pieces" during the reign of Theodosius II.

The next account of the murder was not written until two generations later:

Damascius. Life of Isidore. (5th, early 6th century). He studied in Alexandria and became the last master of the Athenian Academy¹ before it was closed by the emperor Justinian I. He was deeply hostile to Christianity and suggests that Cyril directly engineered the murder. He disagrees with Socrates on the place of the murder and gives no other details. The original is lost and has been reconstructed from fragments quoted by others (e.g., Suda Lexicon, 10th cent.). He provides no thoughtful characterization, no description of her philosophy, no review of her writings.

Damascius. Life of Isidore. (5th, early 6th century). He studied in Alexandria and became the last master of the Athenian Academy¹ before it was closed by the emperor Justinian I. He was deeply hostile to Christianity and suggests that Cyril directly engineered the murder. He disagrees with Socrates on the place of the murder and gives no other details. The original is lost and has been reconstructed from fragments quoted by others (e.g., Suda Lexicon, 10th cent.). He provides no thoughtful characterization, no description of her philosophy, no review of her writings.

For

when Hypatia emerged from her house, in her accustomed manner, a throng

of merciless and ferocious men who feared neither divine punishment nor

human revenge attacked and cut her down, thus committing an outrageous

and disgraceful deed against their fatherland. (Damascius, preserved in the Suda Lexicon)

Note:

1. Athenian Academy. Some writers have described this as Plato's Academy and Damascius as its last master, but there was no organizational continuity between Plato's Academy and the one headed by Isidore and Damascius. These ancient schools were not established and chartered as self-sustaining entities like medieval universities and corporations. For Synesius' visit to Athens nearly a century before, see his Letter 136.)

All other accounts are significantly later:

John Malalas. Chronographia. 6th century. Antioch.At that time the Alexandrians, given free rein by their bishop, seized and burnt on a pyre of brushwood Hypatia the famous philosopher, who had a great reputation and who was an old woman.The stoning with roofing tiles and dismemberment [by dragging?] has been collapsed into the cremation of her body, making it sound as if she had been burned to death. The interesting tidbit is that Hypatia was "an old woman," which accords with Synesius, his letters, and the life of Theon her father. Otherwise, all specific information on Hypatia has vanished from the account.

Except for the history of Justinian and his immediate predecessors, the Chronographia, a pop history for the masses, is "a curious farrago of fact and fancy" and "possesses little historical value." (E.g., In the section preceding the account of Hypatia, John tells us confidently that Atilla was a Gepid and was defeated by the Romans and Goths in a battle on the Danube, in which Atilla was killed. So we see he was not strong on details.) John was a Syriac Monophysite relying on Nestorian sources. The work was reconstructed from multiple successor translations into Slavonic and then in to Georgian plus a single surviving epitome.

Hesychius of Miletus. Onomatologus. 6th century.

Hypatia, daughter of Theon the geometer and philosopher of Alexandria, was herself a well-known philosopher. She was the wife of the philosopher Isidorus, and she flourished under the Emperor Arcadius. Author of a commentary on Diophantus, she also wrote a work called The Astronomical Canon and a commentary on The Conics of Apollonius. She was torn apart by the Alexandrians and her body was mocked and scattered through the whole city. This happened because of envy and her outstanding wisdom especially regarding astronomy. Some say Cyril was responsible for this outrage; others blame the Alexandrians' innate ferocity and violent tendencies for they dealt with many of their bishops in the same manner, for example George and Proterius.The political struggle documented by Socrates has vanished and we now have a generic supposition that the motive must have been envy of her outstanding wisdom. But this does not explain why other women philosophers were not treated similarly. And yes, there were others.

The original is lost and survives as fragments quoted by others. In this case, a fragment repeated in the Suda. It reports that she was married to Isidore; but Isidore lived in the wrong generation. Hesychius is the only source to name Hypatia's mathematical works. In the Suda it is mashed with Damascius' account.

John of Nikiu. Chronicle. 7th century. The account is two hundred years after the fact.

And

thereafter a multitude of believers in God arose under the guidance of

Peter the magistrate – now this Peter was a perfect believer in all

respects in Jesus Christ – and they proceeded to seek for the pagan

woman who had beguiled the people of the city and the prefect through

her enchantments. And when they learnt the place

where she was, they proceeded to her and found her seated on a (lofty)

chair; and having made her descend they dragged her along till they

brought her to the great church, named Caesarion. Now this was in the days of the fast. And they tore off her clothing and dragged her through the streets of the city till she died. And they carried her to a place named Cinaron, and they burned her body with fire. And

all the people surrounded the patriarch Cyril and named him "the new

Theophilus"; for he had destroyed the last remains of idolatry in the

city.

John

of Nikiu puts the murder right after the ambush at St. Alexander’s, which he calls the church of St. Athanasius. He identifies Peter as a magistrate rather than as a reader. He does not mention the roofing tiles, but claims she was dragged around the city.

(This was a common method used by Alexandrian mobs. In fact, St. Mark

himself was supposedly treated in this way by a pagan mob.) John of

Nikiu is the only early source that calls Hypatia a pagan. He wrote in the aftermath of the muslim take-over and perhaps

like commentators on Hypatia ever since, he is addressing the concerns

of his own time and place and projecting them on the early 5th century. His biases are clear: he regards Cyril as a "monophysite" hero against infidels pagans.

The Chronicles survive in an Ethiopian translation of an Arabic translation of a Coptic original. A local author (Lower Egypt) born during Arab invasion. John may have had access to now-lost records of the Alexandrian church. He follows John Malalas and a second, now lost work.

The Chronicles survive in an Ethiopian translation of an Arabic translation of a Coptic original. A local author (Lower Egypt) born during Arab invasion. John may have had access to now-lost records of the Alexandrian church. He follows John Malalas and a second, now lost work.

Notice that the three main sources disagree about where the mob caught Hypatia:

- Socrates: …waylaid her returning home, and dragging her from her carriage…

- Damascius: …when Hypatia emerged from her house, in her accustomed manner, a throng of merciless and ferocious men … attacked and cut her down…

- John of Nikiu: they proceeded to seek for the pagan woman… And when they learnt the place where she was, they proceeded to her and found her seated on a (lofty) chair

According to some, this lynching shut down philosophy and (more importantly to the Modern mind) natural science in Alexandria. Some have gone so far as to say that it brought on the Dark Ages all the way over in Gaul and Britain, and that if it weren't for the murder of Hypatia we would have bases on Mars by now.

So what really happened in the aftermath of the murder?

Continued in Part VII: The Aftermath

A very late comment -- The Caesareum was actually built by Cleopatra VII, the famous one, to honor the deified Julius Caesar, her previous guy, as well as to give some props to Mark Antony, her current guy. Caesar Augustus apparently changed the Mark Antony stuff to honor himself, and the Julius stuff got changed into stuff deifying himself. (Because Alexandria was in the East, and what was creepy in Rome for a living emperor was okay in the East.)

ReplyDeleteThe obelisks from Heliopolis that are in Central Park and on the Thames? They were re-installed at the Caesareum first.

Not sure what the rededicated Caesareum was called, as a church.

Okay, I found out. The Caesareum was the Church of the Archangel Michael.

ReplyDeleteBishop Alexander (Athanasius' mentor) persuaded the Alexandrians to stop worshipping Augustus (or Julius); and Cleopatra's brass or bronze statue of Julius was removed, and replaced with a big statue of St. Michael.