|

| Hope and change |

“Remember that your enemy is never a villain in his own eyes. This may leave you an opening to become his friend.”

-- Robert A. Heinlein

One of the topics in basic problem solving is that people often resist the solution, even to problems they themselves wish solved. That is because solutions by their nature change something, and change inevitably creates anxiety.

So on the second day of the class, the Marge comes to the training room and finds that the books and table-tents have all been moved around. "Tsk," says she to herself. "The cleaning people have gotten the seating all messed up." And so she picks up her book and table tent and is proceeding to her original seat when she notices the two instructors watching from the back of the room. People resist change? Even so trivial a change as a seating arrangement. And so she returned whither her materials had been shifted, and she took to watching the others as they arrived. A little more than half the students insisted on moving back to "their" seats -- seats that had been "theirs" for but a single day.

Imagine the sort of resistance you get when the change is to something in which people have invested ego, like a scientific theory!

TOF in his own seminars used a game -- "The Pony" -- in which students were read a story about two farmers selling a pony back and forth and asked to reach an answer off the tops of their heads which farmer made a profit and how much. Grouped according to the answers they had given, each group was told to develop an argument why their answer was right. Then a spokesman for each group presented its argument to the other groups. Seldom were these arguments sufficiently persuasive to induce people to change groups. In astonishing shows of solidarity, once people were in a group, they showed an odd reluctance to leave it. And these were groups that had existed for but minutes. How much stronger are the bonds for groups like "Production" and "Maintenance" or "France" and "Germany" or "Islam" and "Christendom"?

|

| Mwah-ha-ha |

Similarly, it is a mistake to suppose that everyone on the same side of a change is there for the same reasons.

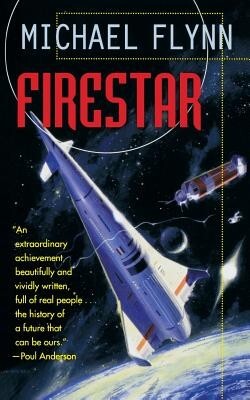

In the Firestar series by an author whom humility prevents TOF from naming, the people supporting the revival of manned spaceflight were doing so in order to:

- fly hot 'chines

- inspire children they were teaching

- save the world from asteroids

- save the environment by doing manufacturing in zero G

- make money in zero G manufacturing

- support women in powerful positions

- etc.

Likewise, their opponents had a mixture of motives; in many cases, the same motives! If the author (and most of his Readers) naturally favor manned space flight, there will be a tendency to depict the opponents as poltroons guilty not only of space-o-phobia but of racism, sexism, and picking their collective noses in public. (One sees frequently antagonists tarred with every such available brush, as if the author wanted to be really-really sure the reader understood that here was a bad guy.)

But in Firestar, et seq., the author tried to show that opponents first of all had motives that made sense and which in some other situation might even be persuasive; and secondly, opponents on one issue might become allies on another. Cyrus Atwood genuinely feared that the economic churning that the new technology would entrain would endanger his beloved nephew's heritage. Phil Albright wound up working with Mariesa van Huyten on several projects, and Mariesa contributed to some of Albright's crusades. And so on. Some reviewers noted that Mariesa's opponents included environmentalists and feminists, but failed to note that her supporters also included these!

Motives and purposes are always mixed. Maculano, the chief prosecutor in Galileo's trial had told Castelli beforehand that he rather thought Copernicanism was true. During the interrogatories, he hardly asked any questions about the motions of the Earth and when Galileo put his foot in his big mouth -- when he said his intention in writing the Dialogues was to disprove Copernicanism! -- he failed to nail his hide to the barn door for the obvious perjury.

The Physics of Characterization

All natural bodies show a tendency to preserve themselves in what they have. For animate bodies, this principle is called "life" (or "soul"). For inanimate bodies, it is called "inertia." We have sayings like- Better the devil you know

- Out of the frying pan into the fire

- Look before you leap

- Fools rush in where angels fear to tread

- Tried and true

- The "Precautionary Principle"

- The status quo already works. At least sorta-kinda. We see this in the evolution of species. The species being supplanted has already been naturally selected! It is already surviving, propagating, doing its thing.

- Most new ideas are bad. Most scientific papers fail to replicate. Most mutations kill the organism. Most new businesses fail in the first few years. If we change the status quo, things are more likely to get worse, not better.

- Oust the czar and get a commissar.

- Storm the Bastille and get a guillotine.

- Hold an Arab Spring and get a Muslim Brotherhood.

- Support a coup in the Ukraine and get an uprising of ethnic Russians.

So given these two things -- it's not so bad + it could get worse -- why would anyone advocate change? Because sometimes the new idea really is better. But inertia means that to make a change requires a force. Not always a physical force, but sometimes even that. Every change of motion requires a mover, an advocate of change.

The Cast of Characters

In change management, we recognize three broad Types: the Innovators, the Conservatives, and the Inhibitors. In marketing, these are called Early Adopters, Late Adopters, and Non-Adopters. These were first described by quality guru Joseph Juran in his book Managerial Breakthrough and again in his seminar Juran on Quality Improvement.

1) Innovators drive change. They are not bound to the past and can be convinced of the change through logic. Their motto is: "Let's boogie!" When they see an old fence, they cry "Tear down that old fence!" But not all innovators have pure hearts. They can grandstand, push pet notions, or be out to make themselves look good. Innovators include:

- Explorers and risk-takers stimulated by the challenge and risk of the unknown.

- Those discontented with the current situation and have little to lose: “Anything would be better than this.”

- Specialists and professionals with an urge to “advance their own specialty.” This is my chance to exercise skills that I have learned. (A jet fighter pilot is likely to support any solution that involves the use of jet fighters.)

- Neophiles will glom onto anything new, even the latest version of Windows, because New!

2) Conservatives are skeptical of change and are bound to the past by results. They can be convinced of the need for change by data. Their motto is: "Show me!" When they see an old fence, they cry "Don’t tear the fence down until we know why it was put up." Conservatives help ensure that something that works is not abandoned -- except when replaced by something better. But they may also demand an exorbitant amount of evidence before coming on board. "More data is needed." Conservatives include:

3) Inhibitors oppose change and are bound to the past by dogma. They cannot be convinced by logic; They cannot be convinced by facts. They cannot be convinced at all. Their motto is "Never!" When they see an old fence, they cry "Old fences are sacred!" At best, they can be bypassed by the advocates of change. In the end, self-interest may bring them around and they will reluctantly hop on the bandwagon just before it leaves town. Max Planck once said that quantum theory ultimately triumphed because all the old physicists had died. Inhibitors include:

- The hard-nosed who want to see concrete evidence of better results. "Give me data," said Sherlock Holmes. "I can't make bricks without straw!"

- The timid, not sure that the new idea really will be better than the old. "This might make things worse!"

- Those comfortable with the status quo. "Why rock the boat?"

- Monopolists who resent any challenge to their perceived rights and status.

- Die-hards who have said the opposite for so long that they can no longer back down without losing face.

- Traditionalists who like the old ways just because they are the old ways.

Most New Ideas are Bad

|

| "This spear can be thrown around corners!" Not all bright ideas are good ones. Most are not. |

This is important for your fictions: It's too easy to suppose that opponents oppose a change even though they see the benefits. They don't. They really are skeptical or really do oppose it for reasons that seem sound to them.

In fact, the history of ideas that have been adopted simply because they sounded good has not been an entirely happy one. That is why history proceeds in two phases:

Phase 1: What can possibly go wrong?Phase 3, of course, is the punishment of the bystanders. "It seemed like a good idea at the time," Robespierre might have said as he was trundled to the guillotine after sending others there for sundry offenses against Reason.

Phase 2: How were we supposed to know?

OTOH, heliocentrism was adopted at a time when there were still fatal empirical objections to it, purely because the math was more elegant. Innovators can be right even before the facts are in.

But how do you know? That's the kicker. You can always point to cases in which Innovators had been right all along, even before the facts were in. But you can also point to cases where the opposite was true. Conservatives are the filter that helps sift the good ideas from the bad. Innovators are liable to regard Conservatives as enemies and lump them in with Inhibitors. But this is a mistake, tactical as well as strategic. Conservatives can be convinced by facts and become allies. The demand for hard evidence helps guarantee that the change really does work better and helps prevent Innovators from making damned fools of themselves -- or worse.

It doesn't always work. Thalidomide went through ten years of controlled field trials in Europe with no problems surfacing, because no one had thought (or dared) to use experimental drugs on pregnant women. That case, an Inhibitor came to the rescue. The then-head of the US FDA had an intuition about Thalidomide and barred it from the US market even though all the data looked good.

|

| Bad Idea even if trains ran on time (which they didn't) |

And it did, until it didn't.

Age of Reasons

There are two kinds of reasons people give for their attitude toward change: their Stated Reasons and their Real Reasons. This is because every change is two changes: a Technical Change and a Cultural Change. The technical change is a change to a procedure, a modification to an equipment, the introduction of a new product, etc. Although there are often germane objections to technical details, this is seldom the big obstacle. The Cultural Change is the booger. |

| The net of culture provides safety: A metaphor stretched to its limits. |

The Parable of the Furniture-Maker. A new hire was introduced to the plant floor at a furniture factory. The Old Bull of the assembly workers took him under his arm and said, "Kid, the quota here is ten pieces per day." Then he shook his head sadly and added, "You can never beat the quota."And so the "new child born into the village" learned the Truth. You Can Never Beat the Quota. The village won't let you. Big Cities may promote loneliness and isolation, but for genuine tyranny, it takes a village.

But the lad knew he could and worked very hard and the very first day he built twelve pieces of furniture. But alas, two were down-checked by QC and he was credited with only ten.

The second day, he again made 12 pieces, but the material handler damaged two with his forklift and once again only ten were credited.

On the third day, two of his 12 pieces simply vanished and no one knew what had become of them. (They showed up several days later when circumstances had slowed production and only 8 units had been built.)

Once upon a time there was a photograph of a meeting between Apple and IBM at which they would collaborate on a new operating system, to be called "Pink," and thereby confound the Devil Incarnate, i.e., Bill Gates. The photograph showed why it would never work. Not because either company lacked programming chops but because all the IBMers were wearing suits, white shirts, and ties while the Apples were wearing t-shirts, jeans, and sandals. No way could these two villages collaborate. They didn't even speak the same language and each found the other's tribal costumes off-putting.

The problem of monocultural aliens or monocultural futures in SF is a topic for another day. Remind TOF sometime that he promised to look into it.

Juran gave an example of an Andean tribe that was visited by a team of agronomists from Lima who had developed a new hybrid maize that would have greater yield than the traditional variety. Much to their surprise, the tribal elders resisted the change and gave a host of technical reasons. Unspoken was the real reason: if the new maize did work as claimed at high altitude, the people in the village would look to the Lima agronomists as the experts rather than to the village elders.

Juran gave an example of an Andean tribe that was visited by a team of agronomists from Lima who had developed a new hybrid maize that would have greater yield than the traditional variety. Much to their surprise, the tribal elders resisted the change and gave a host of technical reasons. Unspoken was the real reason: if the new maize did work as claimed at high altitude, the people in the village would look to the Lima agronomists as the experts rather than to the village elders.Something similar happened when the railroads switched from steam to diesel, eliminating the need for the locomotive fireman. The unions put up a staunch resistance and cited various technical reasons -- we need a second man in the cab because the engineer might suffer a heart attack; because the engineer can only look down one side of the track at a time; etc. (Nor were these reasons totally without merit!) But the real reason, of course was: we're going to lose our freaking jobs! Similarly, the QC manager in a factory resisted a proposal for operator self-inspection and again gave a host of technical reasons: the operators are untrained in using the instruments; they'll fudge the results; etc. As each objection was dealt with a new one arose. The real reason for the opposition was: This will make my QC job less important.

Never expect enthusiastic support for a change that will make that person less important. Sometimes people give up power voluntarily, but they seldom do so willingly.

- An improvement team at a shipyard proposed a simple procedural change that would save the shipyard $10 million per year. Surprisingly, the site manager turned it down. The team learned afterward that the boss was embarrassed at the sheer magnitude of the improvement. How could he tell corporate that this simple improvement had been overlooked for so many years! The team then revised their estimates. The change would only save $5 million/year. For some reason, the boss could live with that. (And they wound up saving $15 million, so go figure.)

- An improvement team at a printing plant solved the problem of dirt streaks in the printing by proposing that commercially available dirt filters be installed on the ink pumps. The plant manager turned them down. Fifteen years before, that manager had been the engineer who recommended removing the dirt filters. (They kept getting clogged with dirt, causing downtime!) The team then let it be known that the old ink filters had been crappy, but technology had moved on and the new kinds of ink filters were much better. This gave the P/M a fig leaf behind which he could approve reversing one of his own past brag-points.

- Two industrial engineers devised a product modification that would improve performance. The design VP turned it down and gave a host of engineering reasons why it would not work. His real reason? Who do these IE's think they are waltzing into Design Engineering and telling us how to do our job? (A year later, Design Engineering introduced the change.)

In each case, the technical objections made no sense to the Innovators because the technical objections were not the real objections. The cultural issues were. The great benefit of the cultural pattern is that it provides predictability, and hence comfort. Things may be predictably bad, but at least we know what to expect. You say this change will make things better -- but we've heard such promises before.

One day, an engineer from a customer plant was brought in to operate the supplier's equipment as part of a cross-training effort between the two. The engineer -- we'll call him Ralph -- was shown a drawer-full of fuses. Every time the machine kicks out, he was told, replace the fuse. After this had happened twice in one shift, Ralph got down and inspected the fuse box. They were using fuses with the wrong rating for that circuit. So he went to the stores clerk and got the proper fuse. The regular operator was very uncertain. That is not the fuse we've always used. If you damage the equipment, your company's on the hook, etc. etc. Of course, the equipment ran for the rest of the week-long exercise without kicking out. But it was interesting the way the regular operators had devised a work-around -- they even knew how many spare fuses to keep on hand -- so they could live with the unacceptable performance.

Sources of cultural resistance include:

- Defense of vested “rights”

- Intrusion by outsiders

- Resentment at having been excluded

- Habit

- Past failures

- Uncertainty

- Comfort with status quo

- Conflicting messages

Rules of the Road

There are a few key notions for characters trying to implement a change. One is to recognize that the change is itself a product of the culture, not a universal truth. (Unless the a change is being forced on the culture by alien invaders or something.) That is, the innovators come out of the same culture as everyone else.

There are a few key notions for characters trying to implement a change. One is to recognize that the change is itself a product of the culture, not a universal truth. (Unless the a change is being forced on the culture by alien invaders or something.) That is, the innovators come out of the same culture as everyone else. Second, remember that the culture provides peace-of-mind through predictability, while change creates stress -- even if it is simply a change in seating arrangements in a classroom. The advocates of change should examine things from the changee's point of view.

And, tempting as it might be, don’t address a local problem with a sweeping master plan. For example, don't use the problem of portability of health insurance as an excuse to overhaul the entire system and replace it with an untested alternative.

| Drop unnecessary bells and whistles |

Work with the recognized leadership of the culture. (These are not always the folks with the titles in front of their names. In one case, during a meeting with the workforce, a consultant noticed that whenever a question came up, the people would glance at two particular co-workers to gauge their reaction and take their cue. The two had no official standing in the hierarchy, but they were people whose judgment the others respected.)

Another way to make a change more acceptable is to weave the change into existing cultural patterns or piggy-back on another, more acceptable change.

An important source of resistance is resentment at being excluded. So provide for participation by everyone affected by the change. If all the affected groups have been involved in developing and testing hypotheses, proposing causes, and debating solutions then the solution belongs to them as well as to the advocates.

|

| Yank me gently |

In the Pits

One of the curious facts in problem-solving is how often the same problem has to be solved again and again. TOF personally knows of a case where fifteen years elapsed between the original solution and the return of the problem like the Mummy of Imhotep arising from its sarcophagus. This is because the changes implemented as the solution are of two kinds: the irreversible and the reversible. TOF will leave it as an exercise for Faithful Reader as to which it is the problem.Juran told a story of a foundry making piston rings for marine outboard engines. One of the causes of the pit scrap turned out to be the amount of molten steel poured by the puddlers into the centrifugal molds. They had been judging the weight by the heft of the long-handled ladles. So the improvement team provided them with scales on which they could weigh their ladles before pouring the steel. Pit scrap began to decline with this and other changes.

But shortly after the team turned its attention to the next problem, pit scrap began to increase once more. When the team investigated they found that some of the changes had been technologically irreversible, but others had not been. In particular, the weighing of the ladles required a change in the work habits of the puddlers and once the focus was off, they drifted back into their older habits of judging the weight by heft. A system of spot checks was implemented to reinforce the importance of the new behavior. Remember: People perform according to what you inspect, not what you expect. If you never check up on something you send the message that it is unimportant. The spot check was maintained until the use of the scales became habituated.

George R.R. Martin does a good job with this in his Song of Ice and Fire series (a/k/a Game of Thrones, et seq.) esp. with Dany Targaryen's troubles in Essos. When the Big Changes come -- killing all the wizards or freeing all the slaves or whatever -- Martin insists on going beyond the Change and showing how things unravel afterward, because there were insufficient steps taken to Maintain the Gain. The essentially autocratic nature of most Advocates of Change comes across with the attitude that all that is required is to say, "Make It So!" and it will be so.

All of which suggests Potential Problem Analysis, a topic for another time.

This is fantastic. I have both bookmarked it for re-reading as part of that rat's-nest of links I refer to as my "writing research," and will be sharing it with my parental units, who are in the business of advertising (another sort of storytelling, really) and often help clients interested in getting people to make changes.

ReplyDeleteI think you handled this issue very well in The Wreck of the River of Stars.

ReplyDeleteThough, if one is writing fiction, wouldn't one want to write it so that the change is handled badly so that there's plenty of conflict going on?

ReplyDeleteNot necessarily. To insist on the change being handled badly is in some cases to *require* an Idiot Plot.

DeleteYou can have all sorts of conflict arising from other sources during a period of change, such as characters disagreeing over the pace of a change. One wants to have the change happen faster, another wants to slow it down (but not to stop it).

And another wants to piggy-back his own agenda on top of the change.

Delete“Suppose that a great commotion arises in the street about something, let us say a lamp-post, which many influential persons desire to pull down. A grey-clad monk, who is the spirit of the Middle Ages, is approached upon the matter, and begins to say, in the arid manner of the Schoolmen, ‘Let us first of all consider, my brethren, the value of Light. If Light be in itself good—’ At this point he is somewhat excusably knocked down. All the people make a rush for the lamp-post, the lamp-post is down in ten minutes, and they go about congratulating each other on their unmediaeval practicality.

Delete“But as things go on they do not work out so easily. Some people have pulled the lamp-post down because they wanted the electric light; some because they wanted old iron; some because they wanted darkness, because their deeds were evil. Some thought it not enough of a lamp-post, some too much; some acted because they wanted to smash municipal machinery; some because they wanted to smash something. And there is war in the night, no man knowing whom he strikes.

“So, gradually and inevitably, to-day, to-morrow, or the next day, there comes back the conviction that the monk was right after all, and that all depends on what is the philosophy of Light. Only what we might have discussed under the gas-lamp, we now must discuss in the dark.”

—G. K. C., Heretics

No matter where you go in the world, there you will find Chesterton, quaffing a beer and laughing.

DeleteCool, thanks.

ReplyDeleteChange examples - At my tiny company, moving from an ad hoc development environment (where the owners decide what they want and tell people to build it) to trying to coordinate several people's development goals and habits with actual customer input. I've long made the mistake of believing that, if I just made a good enough logical case, people would go along. Nope. Even having demonstrable results - having the things I run objectively work better - isn't enough.

1. We're working on a new product. I defined the goals, and laid out a series of steps for research, marketing and development, which I showed to everybody involved, revised on the spot according to their observations and questions, and got them all nodding along.

Next meeting, almost all the issues I thought we'd settled in meeting one came back - it was a disaster. So I took the original plan, boiled it down into a short PowerPoint, met with the two chief designers (who are the key gate keepers - nothing gets done unless they want it done) and took them through it again, slowly, asking for feedback every inch of the way. I also asked what they'd like me to do to help make them happier about the project. Then, I followed up with an email, restating the goals and process, stating what I'd be doing to make them more comfortable, and asking them if I'd gotten it right. They both replied, I made a few clarifications, got them to bless it, and sent out an OK, this is what we're doing email.

Next meeting, the noise was reduced, but not eliminated - several of the basic questions came up again, some even from one of the designers who'd signed off. But it's sort of working, progress is being made. I think. The beta is supposed to be available within 2 months - I drop in on the guy doing the actual design, he now even calls me to get my opinion about look and feel and functionality. I also never miss a chance to tell the people involved how excited I am by what they're doing (it's true) so that they at least get warm fuzzies from me. So, there's that. But experience has me waiting for the other foot to fall.

2. Long ago discovered that one of the chief designers basically hates anything that isn't his own idea. His self-image is tightly bound with being the smartest guy in the room. BUT - if you wait long enough, and stay quiet about it, your ideas will become his ideas, and everything flows nicely from there! I've caused several people who work with this gentleman to laugh out loud when I've mentioned that this is my strategy. The laugh because it's true.

Anyway, have never thought this way about writing - very helpful. I've gotten 75% through with a couple stories recently, where I ceased to be convinced that the characters were sufficiently and correctly motivated to justify the ending - to achieve the level of reader satisfaction that a good ending should achieve. This will help, if I don't murder the stories completely thinking about it.

Now that I've thought about it a while, it occurs to me that the incomparable Marge's fellow students needn't all be resistant to change. Some of them may have had persuasive reasons to select the seats they did the first day, and those reasons still being persuasive, chose the same seat the second day, knowing that the cleaning people wouldn't have been privy to their reasons.

ReplyDeleteNow that I've thought about it a while, it occurs to me that the incomparable Marge's fellow students needn't all be resistant to change. Some of them may have had persuasive reasons to select the seats they did the first day, and those reasons still being persuasive, chose the same seat the second day, knowing that the cleaning people wouldn't have been privy to their reasons.

ReplyDeleteThere's also a lot of punishment for insufficient excitement. If you ask any of the obvious questions about implementation, a lot of times people will assume that you are dragging your feet. Most of the time, I don't really care what the new policy is; and I'll go with any reasonable idea. But I don't want to hear happy talk as much as I just want to know what work activity is associated with it, and how we are going to avoid Things Going Wrong.

ReplyDeleteI mean, I can just make up my own procedures if you like, but if you don't give me any information, then you don't have the right to be surprised if I'm unaware of their effect on other people's procedures. Or contrariwise, if my procedures are really good but other people in my position make up procedures that are really bad.

But apparently, asking questions is negative talk. Sigh.

"What is important is not what people say, but why they say it."

ReplyDelete- Bishop Fulton Sheen