Part I

Looked at the Shroud as an artifact; this part looks at a possible history of that artifact.A Stroll Down Memory Lane

A telling point against the Shroud is that no one seems to have known of it until it surfaced in Lirey, France, in 1349. You would think there'd have been more notice taken of a sacred image! But then, how many people today natter on about the Shroud of Turin, other than enthusiasts and their debunkers? Further, it is not entirely reasonable to hold earlier eras to the standards of modern forensic laboratories regarding chains of custody. We don't doubt Tacitus wrote the Annals even though the earliest manuscript we have of it (M1, from Kloster Fulda) is written in a Carolingian hand (8th cent.), long after Tacitus became tacit, and was itself lost for centuries and rediscovered only in 1506. Who had the original scrolls? Where was M1 during the intervening centuries? How do we know that the Annals and the Histories are not medieval forgeries? (Or perhaps Renaissance fakes!)Simple. We use a double standard. For some artifacts, we allow a reasonable filling-in of the gaps. For other, we do not. Especially if the other has been touted as miraculous, since at that point reflexive dogma kicks in and anything miraculous must be denied. But if we suppose the image on the Shroud was formed by an entirely natural process involving the Maillard Reaction, and the only threatening possibility in play is that it might -- might -- establish the historicity of Jesus and the reliability of certain accounts of his death, we may be able to consider it from an entirely materialistic and secular point of view and make no demands beyond those normally made of ancient artifacts.

Of course, some people may find the simple historicity of Jesus to be threatening enough. That is an entirely different topic.

In fact, few are the artifacts that could satisfy the demands made on this one. All we have in history are isolated data points, and we must as it were "connect the dots," doing the best we can. Let's take a look at one possible reconstruction.

In what follows, TOF has taken accounts from a couple of Shroudie sites, largely because no one else bothers to do this. However, both sites presented information with cautions about reliability and interpretation, and where not, TOF has noted some cautions or omitted the item entirely. For example, there is a Gnotic hymn called the Hymn of the Pearl that seems to TOF to require a great deal of the verbal equivalent of pareidolia to link it to the Shroud at all. And he was unable to find another translation on-line that matched the translation provided at the site, and so TOF does not discuss it here.

Therefore, with the usual standard cautions against the sort of details that have or have not survived the shipwrecks of time, the following reconstruction is offered.

|

| Not an actual photograph of Peter entering the tomb with John |

1. Peter and the Shroud (33-47)

Though the people of the time put more stock in eyewitness testimony than in forensics, if the apostles were going to claim Jesus as risen, the empty tomb and the discarded burial cloths were certainly evidences. Peter, who was first to enter the tomb, did not likely leave the shroud behind. There is no mention of an image on the cloth in the gospel or in Acts.So why was no big deal made about the Shroud at the time? Parchment and paper were expensive well into the Middle Ages, and scribes did not waste writing space on non-essentials. At a time and place when everyone knew from eyewitnesses that Jesus had been seen and heard and guested for dinner after he had died, one needn't hang the winding sheet out the balcony window. It was the resurrection that mattered, not the crucifixion. Besides:

Most Jews (even the more legalistic Jewish Christians) would have been offended by a bloody and imaged grave cloth, and Roman authorities would have destroyed any such evidence suggesting Jesus escaped the death they inflicted. Even gentile audiences might have wondered how attractive the Christian message was when its founder was displayed dead and so gruesomely humiliated. Unless it could be disguised as something else, then there would have been little recourse to hiding it for a more secure time when the Christian message was better understood and appreciated.IOW, the effect would likely have been just the opposite of what our Modern empirical-evidence civilization would expect.

Shortly thereafter Jerusalem became too hot for the Christians. Between 30 and 62 AD, gentile Christians were driven out of Jerusalem, Peter was arrested, and Deacon Steve, Jimmy Zebedee, and James the Just were lynched. Whatever artifacts and writings the Christians possessed would have gone with them when they fled town. Some went south and east into Arabia and Pella, but many went north, to the glittering metropolis of Antioch, the glittering Third City of the Empire.

Athanasius, the later Bishop of Alexandria (ca. 328-373) affirmed that a sacred Christ-icon traceable to Jerusalem and the year 68 was present in Syria in his day:

"…but two years before Titus and Vespasian sacked the city, the faithful and disciples of Christ were warned by the Holy Spirit to depart from the city and go to the kingdom of King Agrippa, because at that time Agrippa was a Roman ally. Leaving the city, they went to his regions and carried everything relating to our faith. At that time even the icon with certain other ecclesiastical objects were moved and they today still remain in Syria. I possess this information as handed down to me from my migrating parents and by hereditary right. It is plain and certain why the icon of our holy Lord and Savior came from Judaea to Syria."

Sed biennium antequam Titus et Vespasianus eandem subverterent urbem, admoniti sunt a Spiritu Sancto fideles atque discipuli Christi…, ut relicta urbe ad regnum se transferrent Agrippae regis, quia ipse tunc Agrippa Romanis foederatus erat. Qui egressi ab urbe, omnia quae ad cultum nostrae religionis vel fidei pertinere videbantur, secum auferentes in has regiones transtulerunt se. Quo tempore etiam icona com ceteris rebus ecclesiasticis deportata usque hodie in Syria permansit. quam ego ipse a parentibus ex hac luce migrantibus mihi traditam iure hereditario usque nunc possedi. haec certa et manifesta ratio est de icona sancta domini salvatoris, qualiter de Judea in Syria partes devenit.One does wish Athanasius had been more specific about "icon." In Greek, it means simply a "picture." No one thought additional details were needed beyond "icon," singular.

-- Athan. opp. II 353c. 36

|

| Not an actual aerial photograph of ancient Antioch |

2. The Church That Was at Antioch (AD 54-200)

Peter ("Rocky") operated out of Antioch from AD 47-54 and was the first bishop of that city, and it was there that the disciples were first called "Christians." The gentile Christians took refuge there until things cooled down in Jerusalem. (And there were disputes between them and the Jewish Christians who had remained in Jerusalem.) Things never did cool down, and Jerusalem was destroyed by Titus in AD 70 and the Jewish Christians were scattered. Titus took some figures of cherubim from the Temple and mounted them on the South Gate of Antioch. The gate therefore became known as the Gate of the Cherubim, and the adjoining district, called "the Cherubim," encompassing the old Jewish Quarter (the Kerateion), was likely the place where the refugees from Jerusalem had settled.

While Jerusalem was honored as the "Mother Church," her bishop was less important than the bishop of Antioch, who presided over the Mother Church of the Gentile Christians. He was given the title Patriarch.

(Three other patriarchs also emerged: the Pope of Alexandria, the Pope of Rome, and -- later still -- the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.)

|

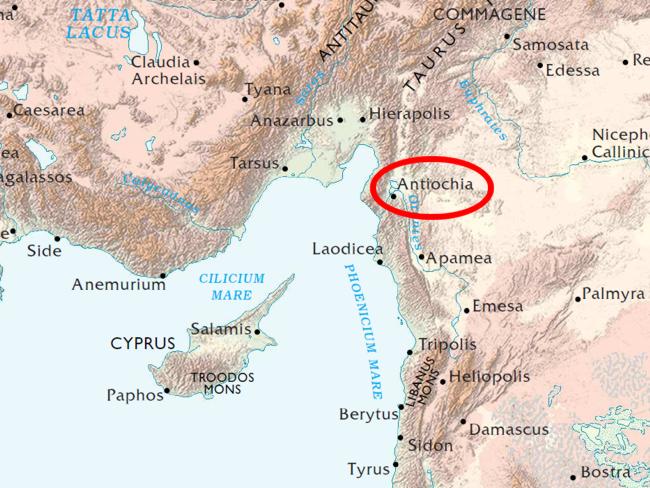

| Crossroads of the Middle East: Lebanon and Palestine due south; Assyria and Persia due east; Anatolia north and west. Note Edessa to northeast; also Damascus, Palmyra,and Hierapolis nearby. |

During the first three centuries of its existence, the Church at Antioch was threatened with extinction through periodic imperial persecutions. Two of its patriarchs are known to have been killed as well. In AD 115, Bishop Ignatius of Antioch, a disciple of the Apostle John, was taken to Rome and killed by wild beasts. During the reign of Decius (249-251), the Bishop of Antioch, Babylas the Martyr, was arrested and died in prison. It was not a happy time to be a Christian, and so the Church flourished -- no doubt because stories of loaves and fishes made up for the wild beasts and the crucifixions.

There were also periods of laizzes faire toleration, such as during the reign of Commodus, but always at the whim or distraction of the emperor.

So why don't we hear of the Shroud during this period? Duh? When the authorities are confiscating and destroying your books and churches, you don't want to let on where anything important can be found, do you? No, you squirrel it away. Even during the intervals of tolerance, you didn't know which way the wind might blow after the next coup or assassination. Unfortunately, this bit of prudence means there is no "chain of evidence" for the Shroud during this period. In fact, very little survives from this period: entire cities are evidenced only by rubble fields, important documents survive only as excerpts quoted by others who did have access to them.

|

| "Fish" carved into marble in ruins of Ephesus (the orange graffito is modern) |

3. Here's Looking at You, King (ca. AD 200)

|

| Icon of Abgar holding the mandylion (encaustic, 10th century, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai). |

This indicates BTW the perils of taking things too literally. The text of Liber Pontificales does say Brittanio rege. But it is not enough for wishful thinking to say, Hey, I bet that's a slip of the pen for Birtha rege! But when coupled with the complete lack of a British Lucius and the known fact that Abgarus the Great, king of Edessa when Eluether was Pope, was in fact surnnamed Lucius, the supposition of an error becomes at the least reasonable.

There is some evidence that Edessa converted to Christianity at this time, which was a considerable coup for the Church. Edessa was a client state technically within the Roman Empire (depending on who was emperor) and at the least sensitive to the desires of Rome. However, speaking of coups, shortly afterward, Septimus Severus became emperor and it was no longer safe to be openly Christian. Lucius Abgar decided there was nobody here but us chickens.

c. AD 250. After Septimus Severus took over, an odd thing happened. A story developed that an earlier Abgar, now safely dead, had written a letter to Jesus asking for healing from a disease, and Jesus had written back sending a cloth with the miraculous image of his face. The king was duly cured. This story first appears in the apocryphal Acts of the Holy Apostle Thaddeus (AD 250), about half a century after Lucius Abgar:

And Ananias [Hanam], having gone and given the letter, was carefully looking at Christ, but was unable to fix Him in his mind. And He knew as knowing the heart, and asked to wash Himself; and a towel was given Him; and when He had washed Himself, He wiped His face with it. And His image having been imprinted upon the linen, He gave it to Ananias, saying: Give this, and take back this message, to him that sent you: Peace to you and your city! For because of this I have come, to suffer for the world, and to rise again, and to raise up the forefathers. And after I have been taken up into the heavens I shall send you my disciple Thaddæus, who shall enlighten you, and guide you into all the truth, both you and your city. And having received Ananias, and fallen down and adored the likeness, Abgarus was cured of his disease before Thaddæus came.

So far as TOF can tell, this is the first mention of a face-image-on-cloth. It is only a face, but the cloth is referred to as tetradiplon,"four-folded," which will come up again later. The yarn may have been the origin of the medieval story of Veronica and her veil.

In the Gospel of Nicodemus, (mid-4th cent.) the woman who was cured of a hemmorhage by touching the hem of the garment was called Veronica and she used the cloth to cure the emperor Tiberius of a disease. (Note the parallel to the curing of Abgar V of a disease.) This later became Veronica wiping the face of Jesus along the Via Dolorosa. Clearly, a story about an image-on-a-cloth was in circulation by then. Or rather, a story was needed to account for an image-on-a-cloth.

c. AD 320. A later version of the Thaddeus story has Thomas, the Twin, send Thaddeus (Addai), one of the 72, to Edessa after the Ascension, and Thaddeus cures the king. This story as recounted in Eusebius' Ecclesiastical History (1.13) (AD 320) and does not mention the cloth with the image. But Eusebius, a major Constantinid suck-up, in a letter to Constantia, Constantine's half-sister, showed himself opposed to images, full stop. Addai is traditionally credited with being the "Apostle to Syria and Persia" by Syrian and Persian Christians, known as the Assyrian Church and the Chaldean rite of the Roman Catholic Church. These are the modern day "Iraqi" Christians currently being driven from their ancient homeland.

c. AD 384. Sister Etheria of Spain (or Gaul) visited Edessa and was shown a copy of Abgar's letter to Jesus (but not the alleged reply from Jesus) and shown the gate whereby Ananias entered the city with the reply. She was not shown a cloth with an image. So if it existed, it was no longer in Edessa, since it would have been logical at that point to say, "And here it is!" The Travels of Etheria is the first major literary work by a woman author in Western history.

c. AD 400. Eventually, the image "not painted by hands" becomes exactly that in a Syriac manuscript evidently derived from the Acts of Thaddeus. The Doctrine of Addai says:

When Hannan, the keeper of the archives, saw that Jesus spake thus to him, by virtue of being the king's painter, he took and painted a likeness of Jesus with choice paints, and brought with him to Abgar the king, his master. And when Abgar the king saw the likeness, he received it with great joy, and placed it with great honour in one of his palatial houses.Notice how in a century and a half, the image has changed from one made miraculously by Christ to one painted by Ananias/Hannan, albeit with "choice" paints.

The Abgar story is untenable for a variety of reasons (including the wording of the alleged letters). But if the time between Commodus and Constantine was especially hazardous for Christians, it is certainly possible that a real event ca. AD 250 was disguised by being altered into an "old legend" set ca. AD 30. On this allegorical reading:

Abgar V writing to Jesus about a physical ailment was Agbar the Great writing to Pope Eluether about a spiritual ailment, and that the cloth sent by Jesus was the Shroud kept in nearby Antioch sent by the Patriarch, which Aviricius, not Addai, brought to Edessa.The singular peculiarity is that by the third century there is talk of a cloth with the image of Jesus on it, associated with the city of Edessa. But why talk about an image-on-a-cloth at all? There is nothing in the Bible about it. It's not like Acts of Thaddeus lacks for miraculous cures without an image. If the story was made up out of whole cloth (ROFLOL!) why make up that story instead of another one? One possibility is to provide an "explanation" for an actual image.

If there was a cloth with the Lord's face on it, it was probably kept in Antioch and returned there after Aviricius borrowed it for the Big-Name Conversion. If it had still been in Edessa, the bishop would have shown it to Sister Etheria, since by AD 384 it was relatively safe to do so.

4. Meanwhile Back in Antioch (200-362)

The interlude from Septimus Severus to Diocletian was, if anything, more terrible than the intermittent persecutions from Nero to Marcus Aurelius. The Empire was falling apart and political loyalty became even more enmeshed with the public rituals that were called religio, or "re-binding." Previously, the Empire had not gone hunting for Christians, but simply executed them if they were denounced to the authorities and refused to recant. Now, under Diocletian, they did go hunting. Imperial harmony was predicated on creating a syncretic religion by blending elements of all religions into one. The Jews and the Christians demurred.From 303 to 305, during the short but intense Great Persecution, Diocletian destroyed churches and scriptures and banned Christian worship. Many Antiochenes were martyred, and their bishop was condemned to the marble quarries of Pannonia. "There was so great a persecution," reads the Epitome Feliciana, compiled no later than AD 530, "that within 30 days 16,000 persons of both sexes were crowned with martyrdom as Christians in various provinces."

quo tempore fuit persecutio magna, infra XXX diebus XVI milia hominum promiscui sexus per diuersas prouintias martyrio coronarentur.Galerius continued the Great Persecution in the eastern Empire until 311, and at Antioch, the site of his imperial residence, he had martyrs slowly roasted over open fires. The decrees of Diocletian and Galerius included the confiscation and destruction of all Christian books and treasures, a sufficient reason one would think for squirreling away whatever they could. If the burial shroud of Christ had been kept in Antioch until then, it would have either been confiscated and destroyed or else securely hidden.

-- Epitome Feliciana XXX Marcellinus

Meanwhile, the Caesar of the West, Contantius Chlorus, did not enforce the anti-Christian pogrom. His son Constantine would go a step further when he and Licinius agreed in AD 313 to recognize Christianity as a legitimate religion and tolerate its practice. Eventually, Constantine built basilicas in Jerusalem over the Holy Sepulcher and the Golden Basilica in Antioch.

5. The Empire Strikes Back

|

| Julian the Apostate, a bit miffed because his cousin massacred his whole family. |

Time to hide the relics again! Damn, just when you thought it was safe to go back in the waters of public life.

October 22, 362. When Julian visited Antioch, a fire in the Temple of Apollo damaged its roof and a statue of the god. This would do for a "Reichstag fire" and Julian blamed it on the Christians. He ordered Constantine's Golden Basilica closed and its vessels and (surprise!) its treasures confiscated. (He was planning an invasion of Persia and needed cash.)

"One priest, Theodoritus by name, alone did not leave the city; Julian [the uncle of Julian imp.] seized him, as the keeper of the treasures and so able to give information concerning them, and maltreated him terribly; finally he ordered him to be slain with the sword, after he had responded bravely under every torture."One likely place for Theodore to have hidden the treasures of the Basilica was under the protection of the cherubim; that is, in a niche in the city wall in the Gate of the Cherubim. Theodore would have done the hiding ca. AD 362.

-- Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History Book V ch.8

6. The Cherubim Gets a Religious Rep (362-540)

At this point, the only one who knew where the treasures of the Golden Basilica were hidden was dead as a doornail. If the image-cloth mentioned in the Acts of Thaddeus (and retro-dicted onto an earlier age) was squirreled away in the Cherubim, no one likely knew about it. (Or an Indiana Jones-like secret society was guarding it! Woo-woo!) | |

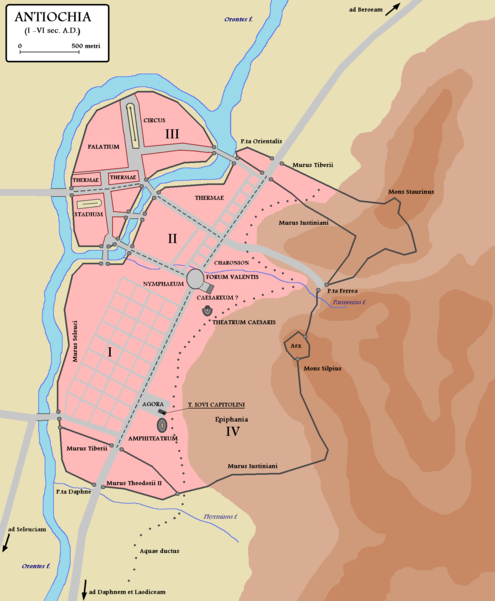

| Sixth cent. Antioch. Gate of Cherubim: southern gate in the inner (Tiberian) wall. The Cherubim district would be just inside. The Golden Basilica was on the island at the upper left. |

Re: Hidden treasures. In 1146 Turkish forces destroyed the Christian civilization in Edessa, and Turkish looters spent a year digging up that town, searching secret places, foundations and roofs. "They found many treasures hidden from the earliest times of the fathers and elders, and many treasures of which the citizens knew nothing." So it's not unbelievable that the earthquake (or an earlier flood) popped open some hidden trove in the Gate of the Cherubim in Antioch.

ca. AD 527-533. And indeed, from this time, the Kerateion was regarded as having special religious associations because it possessed an image of Christ which was an object of particular veneration. The Greek term is eikon and this can refer to any sort of image whatsoever. The Life of Symeon Stylites the Younger, born shortly before the earthquake and raised in the Cherubim, reports that he witnessed the appearance of Christ "at the old wall called that of the Cherubim."

c. AD 550. It was also at around this time that earlier images of Christ as a beardless Greco-Roman youth were superseded by more realistic images of a Semitic Christ with moderate beard, mustache, shoulder length hair parted in the middle, etc. and often rigidly front-facing. These new depictions also sometimes included peculiar features shared with Shroud Man -- such as an open top square on the forehead, one or two “V” shaped markings near the bridge of the nose, a raised eyebrow, accentuated cheeks, enlarged nostril, hairless area between lips and beard, and large owlish eyes. Among the earliest are Byzantine mosaics at Ravenna (c. AD 540) and the icon at St. Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai (c. AD 550). Note that this artistic revolution occurred within a decade or two after the reputed discovery of the Edessa Cloth. A number of icons purporting to be copies of the "Cloth of Edessa" began to circulate shortly afterward.

One possibility is that the medieval trickster based Shroud Man on these by-then universal Byzantine artistic tropes. But the latter raises the question: on what was the sudden change in artistic renderings based? It may be that the new depictions were based on the re-discovered Shroud Man rather than vice versa.

|

| Christ Pantocrator Icon at St. Catherine's Monastery |

|

| Shroud Man |

John Moschos, a Byzantine monk of the sixth and seventh centuries, relates an old incident involving a Kerateion social worker who had chastised a poor man for having obtained four linen undergarments:

The next night, the supervisor of the social service saw himself standing in what is called the Place of the Cherubim. It is a very sacred place and those who know say that in that place there is a very awesome icon bearing the likeness of our Saviour, Jesus Christ. As he stood there in deep thought, he saw the Saviour coming down to him out of the icon and censuring him especially on account of the four garments which the poor man received. Then, falling silent again, Christ removed the tunic he was wearing and showed him the number of under-garments while saying: ―Behold, two; behold, three; behold, four. Do not be dismayed; inasmuch as you provided those things for the poor man, they became my raiment.A vision involving Christ having four linen undergarments? WTF? What has that to do with a linen cloth bearing an image of Christ folded four times?

7. Off to Edessa!

AD 540. Then along came the Persians. Justinian's armies were off reconquering Italy from the Goths, so the Persians decided it would be a good time to invade because like the Romans did not have enough problems just then. The Roman and Parthian/Persian empires fought again and again over the centuries. The long-term results were always status quo ante bellum. Never has so much blood been spilled for so little effect. In retrospect, this would eventually weaken both empires just in time for the Arab invasions. Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time.*

(*) Byzantium vs. Persia. A tradition continued by the Sunni Ottoman Turks and the Shi'ite Persians.

Justinian sent small army to Antioch to assess the situation and they found themselves vastly outnumbered. So they assessed that they should get their assesses out of there. The army (along with sundry citizens) evacuated the city through the Gate of the Cherubim, which had not yet been invested. The remaining citizens of the "free city of Antioch" put up a solid resistance but were overwhelmed by the Persians, who then as a reward ordered the whole city razed to the ground and the inhabitants sold into slavery. Only the Golden Basilica with its earthquake-damaged dome was spared, since the cathedral chapter piled all the gold and silver vessels in a circle around it for a ransom, a more protective wall than bricks and mortar. The rest of the great City of the Empire was burned and looted. (Evagrius IV ch.5)

The city never recovered from the double-whammy of earthquake and conquest, though the Romans, after re-taking the city, never stopped trying. The rebuilt city, renamed God-town, was smaller and less populous, but it dragged along until the Turks reconquered it from the Crusaders in a later age, and ordered everyone in it killed and the city razed to the ground. Again.

It is at this point that the Holy Image of Edessa makes its appearance, complete with a spurious connection to the image of Abgar and a purported rediscovery of the cloth in a niche of the walls of Edessa. But, given that Sister Etheria had been shown no such image back in the day when it would have been logical to have been shown her, it seems safe to assume the image had not been kept in Edessa previously. The discovery of the cloth in the wall of Edessa is likely an adoption of such a discovery in the wall of the Cherubim Gate in now-derelict Antioch.

Now, where do you suppose the Persians went after destroying Antioch? That's right, they went to Edessa! And there, Chosroes ordered his troops to build an aggestus, a mound of earth and timber that would overtop the city walls "so the besiegers could hurl their missiles from vantage ground against the defenders." Evagrius Scholasticus tells us what happened (Book IV, ch. 27).

When the besiegers saw the mound approaching the walls like a moving mountain, and the enemy in expectation of stepping into the town at day-break, they devised to run a mine under the mound and by that means apply fire, so that the combustion of the timber might cause the downfall of the mound. The mine was completed; but they failed in attempting to fire the wood, because the fire, having no exit whence it could obtain a supply of air, was unable to take hold of it. In this state of utter perplexity, they bring the divinely wrought image, which the hands of men did not form, but Christ our God sent to Abgarus on his desiring to see Him. Accordingly, having introduced this holy image into the mine, and washed it over with water, they sprinkled some upon the timber; and the divine power forthwith being present to the faith of those who had so done, the result was accomplished which had previously been impossible: for the timber immediately caught the flame, and being in an instant reduced to cinders, communicated with that above, and the fire spread in all directions.

Chosroes lifted the siege and withdrew from Edessa.

The notable point is not how the image was made or how it came to Edessa, a tale which seems to have suffered from the long game of telephone and fallen into legend, but from the actual physical presence of such a cloth image in Edessa after 540, and that the image was sufficiently strange to contemporaries that it was not believed the work of the hands of men. This would not have been the case had it been merely a painting.

6th cent. The Syriac Acts of Mar Mari the Apostle records the miraculous origins of the Icon and probably dates to the 6th century. In it Jesus is said to have made his image on a sdwn’ (linen cloth).

The history of Edessa can be summarized as follows:

602/603 -- captured by the Persians;

604/605 -- recovered by the Romans

611 -- recaptured by the Persians

627 -- Persians evacuate per treaty

638 -- surrenders to the muslims

8. Under Muslim Rule

AD 639. After the Persians had come, gone, come and gone again and the Byzantine Romans had gone, come, gone and come again, the city of Edessa was conquered by the muslims and has remained in the House of Submission nearly ever since.* However, the early Arab conquerors respected the Hellenic and Christian heritage of the civilized lands they took possession of. Christian monks like John of Damascus even served in the Caliph's court.

(*) ever since: briefly, the Crusader County of Edessa. Presently, the Turkish town of Urfa.

|

| Himation. You should see the Hermation! |

Abgarus sent envoys to ask for His likeness. If this were refused, they were ordered to have a likeness painted. Then He, who is all-knowing and all-powerful, is said to have taken a strip of cloth, and pressing it to His face, to have left His likeness upon the cloth, which it retains to this day.The implication is that Edessa still had the cloth, which was referred to by Johnny D. as a himation, a long rectangular cloth worn as sleeveless garment in ancient Greece and well and the Greek Byzantine era. It would be about the size and shape of the Shroud of Turin.

AD 700s. There were other comments on the Edessa Image:

- Andrew of Crete describes the Image as “the imprint … of the bodily [somatikou] appearance” of Christ, an interesting departure from those versions mentioning only a face

- Athanasius bar Gumoye comments that a painter making a copy of the Image had to "dull" his colors to match it.

- Patriarch Germanos (A 9th century writer in Constantinople) a description of the Image’s face as "sweat-soaked." Other contemporary texts also use this same description.

c. AD 755. Somewhat later, out west, Pope Stephen III (752-757) is said to have claimed in a sermon that he had "often heard the story from those coming from the eastern parts" that:

this same mediator between God and men [Christ], in order that in all things and in every way he might satisfy this king [Abgar] spread out his entire body on a linen cloth that was white as snow. On this cloth, marvelous as it is to see . . . the glorious image of the Lord’s face, and the length of his entire and most noble body, has been divinely transferred.This is interesting because it implies a full-body image. Others have claimed that the passage is a later interpolation, sometime prior to AD 1130. Why an anonymous medieval hoaxer made a fake shroud with near miraculous secret processes and then added a description of it to an obscure older document so that it could be found in the 20th Century to provide bona fides to the 14th Century fraud is left unexplained. If one is to believe in miracles, this would be a good place to start. In any case, "before 1130" is still earlier than the radiocarbon dating on the Shroud. TOF cannot say anything more, since he has no idea what ol' Steve-3 really wrote, not having access to the original text.

There are a number of other references to the Image of Edessa in Syriac texts preserved by the Assyrian and Georgian churches, such as that Theodosius, a monk from Edessa, was “a deacon and monk [in charge] of the Image of Christ.” Again, implying something singular about "the" image.

AD 723. Manuscript BL Oriental 8606 dated to 723 refers to the Church where the image was kept as "The House of the Icon of the Lord."

AD 787. The Second Council of Nicaea took note of the Edessa Icon several times. The bishops were concerned with making a distinction between veneration of images (proskynesis) and worship (lateria).

Early 800s Theodore Abu Qurrah wrote:

"As for the image of Christ … it is honored by veneration especially in our city, Edessa, the blessed, at definite times, with its own feasts and pilgrimages."Early 900s. Alexandrian Patriarch Eutychius writes of the Image:

"the most wonderful of His relics which Christ has bequeathed to us is a napkin in the Church of ar-Ruha [Edessa] …. With this Christ wiped His face and there was fixed on it a clear image, not made by painting or drawing or engraving and not changing."So the Image of Edessa was widely regarded not only as an image, but as the image of Christ, and was widely reputed to be not a painting or drawing. It was also regarded as a smaller cloth showing only the face -- but one would expect this if the Shroud were folded four times and then placed behind matting in a special case with only the face showing.

Remember Tetradiplon? The Acts of Thaddeus referred to the cloth as tetradiplon, which means "folded in half four times. If the Shroud is folded in half four times, as shown below only the face will show. And if this is then enclosed in a matting on either side, it will look like a portrait on a small mandylion.

If the Shroud is folded tetradiplon, you get a face on a

"landscape" orientation, as shown in the 10th cent. painting

of "Abgar" receiving the image.

The fold marks, TOF has read, are still discernible.

|

| Flabella are still used in Orthodox liturgies |

IOW the Image of Edessa was almost always kept folded and hidden away from prying eyes, just like the Shroud during later centuries in Turin.

10th century. A manuscript Vossianus Latinus Q69 found in 20th cent. in the Vatican Library contains the oldest Latin version of the Abgar Legend. It asserts that the Edessa Image was of Jesus’ full-body and may derive from a Syriac text even before 769. In this version, Jesus denies Abgar’s request for a visitation, but writes he will send him a linen "on which you will discover not only the features of my face, but a divinely copied configuration of my entire body." It quotes a man called Smera in Constantinople: "King Abgar received a cloth on which one can discern not only a face but the whole body" ([non tantum] faciei figuram sed totius corporis figuram cernere poteris.) The story then continues:

[Jesus] spread out his entire body on a linen cloth that was white as snow. On this cloth … the glorious features of that lordly face, and the majestic form of his whole body were so divinely transferred …. This linen, which until now remains uncorrupted by the passage of time, is kept in Syrian Mesopotamia at the city of Edessa, in a great cathedral.Note the similarity to the sermon ascribed to Pope Stephen earlier. For all TOF knows, this is the document in which Stevie's sermon can be found, in which case, the comment is no later than 10th century. There is also the suggestion of a miracle:

on Easter it used to change its appearance according to different ages: it showed itself in infancy in the first hour of the day, childhood at the third hour, adolescence at the sixth hour, and the fullness of age at the ninth hour, when the Son of God came to His Passion … and … cross.One possibility is that this describes the gradual raising of the entire shroud from its chest on this one day of the year, showing first only part of the image and progressing to the full "passion" image. (Behold, two; behold, three; behold, four as the linen unfolds.) But this is pure speculation.

9. The Image of Edessa Goes to the Big City

|

| The emperor embraces the cloth in a Syriac drawing. This may be the handing-over of the cloth to the Romans (who are actually Greeks, but they called themselves the Romans to the bitter end.) |

John laid siege and raided the neighborhood until the emir decided to trade the Image for Byzantine cash, freed prisoners, a promise of permanent peace, and a right-handed pitcher to be named later. The Syriac Christians were none too pleased that their muslim overlords had bartered away their religious claim to fame, nor (being themselves Monophysite) that the freaking homoousian Orthodox had taken possession of their prized relic. They tried slipping over a couple of substitutes, and then being caught in the act, demonstrated and jeered as the Byzantines marched out of town with the goods.

On August 15, 944, the Image arrived in Constantinople where it was received with great fanfare and placed in the Church of St. Mary Blachernae in the city’s northwest corner. After celebrating the Mass for the Assumption of the Virgin, a small group of clergy and nobility previewed the celebrated image. There are three accounts of of this event:

- The Narratio de imagine Edessena,

tells us that future emperor Constantine VII described the image as

"extremely faint, more like a moist secretion without pigment or the

painter’s art."

- Symeon Magister’s Chronographia explains that

Constantine VII could see some image features but his brothers-in-law (two "ruffian" sons of the emperor, Romanus Lacapenus) could barely see any image at all. Constantine was trained as an artist.

- Gregory Referendarius, the archdeacon of Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia cathedral, gave a sermon in which he described the cloth as having an image, the likeness of a man, seemingly formed by sweat. He also mentions bloodstains and seems to mention a side wound.

This reflection [Jesus’ image] … has been imprinted only by the sweat from the face [of Jesus], falling like drops of blood, and by the finger of God. For these are the beauties that have made up the true imprint of Christ, since after the drops fell, it was embellished by drops from his own side. Both are highly instructive – blood and water there, here sweat and image. .... the origin of the image made by sweat is in fact of the same nature as the origin of that which makes the liquid flow from his side.Naturally, there is controversy. Gregory's there and here might have been referring to the gospel text and he may not have been pointing to the displayed Image he was praising. If he had been, the implication of the side wound is that the whole body was visible on the image.

But the intriguing thing is the description of the image as being blurry, made of sweat, faint, etc., which would certainly describe the image on the Shroud of Turin. No wonder someone making a copy would have to "dull his colors." We can imagine that these Byzantine grandees, accustomed to the bright-colored art of their milieu, might actually have been disappointed. This is the divine image "not wrought by human hands? For this we paid the emir of Edessa a pile of gold? Why, he's... he's naked! And the image is crappy! You can barely see it! Surely God would have been more expert -- and more modest -- in making an image of himself! We were cheated!

The very features that we Moderns might take as persuasive would have seemed to them to argue against the image. Had the image shown a figure with right hand raised in blessing, wearing at least a loincloth, and splendidly colorized, the Byzantines would have nodded and taken it in stride; but the Modern would shake his head and say, That ain't no grave cloth, but an obvious artifact.

In particular, Naked Jesus was a problem -- to the Syriac Christians especially, but also to the Greeks. (The Latins were more blase about dead naked bodies -- in a few centuries they will be doing medical dissections.) This may be why the image was folded up with only the face showing and the cloth was seldom displayed to the public. Whereas we (and the Latins) would have displayed the whole image, Oriental Christendom was more reserved and kept it in a box.

Besides, by this time both Greek and Syriac were heavily invested in the Agbar legend and it would be embarrassing to admit that the Image was something very different from what they had always thought. Not a cloth with which the Lord wiped his face in the Garden (as the then-current version had it) but the burial linens with a full monte.

But oddly, the "burial linens of Christ" do start showing up in imperial relics lists at about this time, alongside the Mandylion face-cloth. Were there two relics? There is no record of a public celebration for the burial linens as there is for the Image of Edessa. And some accounts refer to the cloth as bearing a face and others as bearing a full body image.

10. Life in the Big City

During its residence in the Big Apple, the Image and/or Shroud make many appearances. The imperial palace, the Boucoleon, stood in the southern district of Constantinople, near the shore of the Bosphorus. One of the churches there was the Pharos (Lighthouse) which acted as sort of Relic Central.AD 958. A list of Passion relics in the imperial treasury mentions the "burial linens" of Christ.

In times of danger, processions would carry some of these relics through the City to the Church of the Virgin at Blachernae, which was in a the north of town and a rallying point in times of trouble.

AD 1037. A severe drought threatened the City and Emperor Michael IV personally carried the Image of Edessa in procession to Blachernae to plead for rain. In the Dodekabiblos (Twelve Books) of Dositheos: 'Theophanes and Kodinos say that when Michael the Paphlagonian was emperor there took place a litany in which the first of the emperor's brothers carried Jesus' letter to Abgar, and the second the spargana of Jesus'. Spargana literally means swaddling clothes, but in the liturgical language of the Orthodox Church entaphia spargana means burial wrappings. Since we would normally expect the Mandylion to have accompanied the letter of Jesus to Abgar, it seems possible that the Mandylion and the entaphia spargana (burial wrappings) were one and the same.

AD 1081. A letter purportedly from Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus to Robert of Flanders, pleading for Western assistance against the Turks, runs:

Among these precious relics, he lists “the linen cloths found in the sepulcher after his resurrection.”So, for the love of God and piety of all Greek Christians, we beg you to bring here whatever warriors true to Christ you can find in your lands, the powerful, the less powerful and the insignificant....Therefore, you should make every effort to stop them capturing Constantinople, thus ensuring that you will gain the joy of glorious and ineffable mercy in Heaven. Given the immensely precious relics of the Lord to be found in Constantinople, better that you should have it than the pagans.

Eventually, the Latins got up the "first crusade" in response. But the letter is thought by some to be a forgery, and among the precious relics, Alex also names:

- the head of John the Baptist complete with hair and beard,

- fragments left over from the five loaves and two fishes,

- a large piece of the true cross,

- the pillar to which Jesus was tied during his scourging and

- the whip that was used.

However, foreign visitors and pilgrims in the 11th and 12th centuries left several reports of the “linen cloth with the Lord’s face on it,” but noted that the relic was kept hidden and available only to the emperor. There are scattered reports or hints of a full-body image.

AD 1125. An English pilgrim to the Great City recorded the cloth sent to King Abgar containing "the face of the Savior without painting," and also numerous relics from the Christ’s Passion including "the linen cloth and sudarium of the entombment." So were there one or two linens?

In the Menaion (Monthly Calendar), an Eastern Orthodox liturgical book, the following passage appears for the date of 16th August, the Feast of the Holy Mandylion:

"When you were alive you imprinted your face on a sindona, and when you died, at the end of your life, you entered a sindona"This seems to be an effort to reconcile a full-body image on the shroud ("entered" a sindona) with the Agbar legend ("imprinted your "face").

AD 1130. English monk, Ordericus Vitalis, in his "History of the Church" describes the Edessa Icon (now called the Mandylion) as "displaying the form and size of the Lord’s body."

AD 1157. Icelandic Bishop Nicholas Soemunundarson visits the Big City and reports both a mantle (mandylion) and sudarium, presumably a burial linen. But both cloths were considered so sacrosanct only top level nobility and clergy were likely to be able to peer into the golden vessels where they were hidden.

AD 1171. Emperor Manuel I Comnenus shows Amaury I, King of Jerusalem, "the cloth which is called sisne in which he [Jesus] was wrapped."

12th cent. Englishman Gervase of Tilbury, a world traveler and author of Otia Imperialia, reported a doubtful tale current in city lore. Joseph of Arimeathea supposedly rebuked the holy women at the cross for allowing Jesus to hang naked in death, so they

… quickly bought a spotless linen so large and long that it covered the whole body of the crucified Christ. And when the body hanging on the cross was taken down, there appeared imprinted on the linen an effigy of the whole body.

|

| Threnos showing Christ being laid on a body-length linen. |

During this time, three new motifs appear in Byzantine art.

- Threnos (Lamentation) scenes: show Mary, Joseph of Arimathea, Nicodemus, John, and/or angels grieving over a near naked Christ laid out on a long burial linen at the foot of the cross. Earlier forms had depicted a completely covered, mummy-wrapped Christ being carried into the tomb. These scenes often include "Turin Shroud characteristics."

Epitaphios (“on the tomb”), occurring about this time or later in the 12th century, had an unclothed dead Christ pictured on a liturgical cloth used by the Orthodox on Good Friday.

Basileus tes doxes:

Christ-in-a-box

Very strange pose.- Basileus tes doxes (“King of Glory”) shows the dead Christ, often only from the waist up, standing in a box. Some of these boxes are obviously meant to represent a sarcophagus, but others are much too small and narrow for that purpose. Called the Christ of Pity in the West.

|

| The Pray codex and its herringbone shroud Named for historian György Pray |

2. The unusual three-hop herringbone weave

3. Jesus is shown naked with his arms folded at the wrists

|

| L-shape burn holes on Shroud |

5. Less clear, a mark on Jesus’ forehead where the most prominent bloodstain ("3"-shaped) is found on Shroud Man's forehead.

|

| L-shape of holes in Pray Codex |

If the shroud is folded into quarters, the four sets of poker holes line up and the magnitude of the burns shows which was the top and bottom folds, since one of the holes does not go all the way through. Hate to be the acolyte that let an incense spark fall on the linen! (Images of the holes can be found in the STURP library, here. You have to scroll to find them.)

AD 1201. Nicholas Mesarites, the skeuophlax (overseer) of the relic collection in the Pharos Chapel, deters a mob rampaging through the Boucoleon grounds from plundering the many sacred objects kept there. According to Mesarites these included the

burial sindons of Christ [which were] of linen … of cheap and easy-to-find material, still smelling of myrrh, and defying destruction, since they wrapped the uncircumscribed, fragrant with myrrh, naked body after the Passion.Mesarites then declares, "In this place [relic collection chapel] He [Jesus] rises again, and the sudarium and the burial sindons are the proof." That is certainly an odd thing to say.

11. Hard Times in the Big City

During an otherwise normal episode of Byzantine treachery, overthrow, and vendetta, the nephew of the ousted Roman Emperor invited an army of crusaders who were begging their way toward Jerusalem to help put his uncle back on the throne. The people clamored for him, he said. (See "mob," above.) And if the crusaders helped, then the wealthy Roman Empire would fund the rest of their crusade.Well, okay. You didn't have to tell crusaders twice! They'd been having a rough time of it and had already been diverted once, to take an ex-Byzantine city away from the Hungarians, for which their leadership had been excommunicated by the Pope. (All but Simon Montfort, who declared the affair dishonorable and had taken his marbles and gone home.)

It turned out the nephew lied. The people did not welcome Uncle back; and the generals weren't too jazzed about a bunch of Venetians and Franks running around the City. One may as well invite hillbillies to the Upper East Side. So the crusaders were told to camp outside the city, and they would be paid Real Soon Now. A few went into town and committed tourism.

|

| How the Shroud raised itself upright. |

… another church called My Lady St Mary of Blachernae, where there was the shroud [sydoines] in which Our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday raised itself upright, so that one could see the figure of Our Lord on it...WTF? The Shroud raised itself upright?

So what did Mesarites mean when he said

"In [the Pharos chapel] He rises again, and the sudarium and the burial sindons are the proof"or de Clari when he wrote

the shroud in which Our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday raised itself upright, so that one could see the figure of Our Lord on it...The simple mechanical contrivance proposed by Wilson (see drawing) would raise the tetradiplon from its box like the Lord rising from a tomb. And not incidentally like the Basileus tes doxes or "King of Glory" art motif that had spread in the preceding century.

AD 1204. The starving crusader army finally got tired of waiting to be paid. The Uncle had been ousted a second time, the nephew was on the throne and was having a hard time remembering his promises. Turns out: the Empire is dead broke due to the various thugs, numbnuts, and kleptomaniacs who had been running it, and the clueless military generals were disinclined to give what little was left in the treasury to a bunch of rednecks.

But in the war of snobs and rednecks, guess who wins? The crusaders find an old passage -- a sewer, iirc -- and a single Frankish knight wriggles inside the walls to find himself facing the entire Byzantine Army. He goes BOO! and the entire Byzantine Army runs away. Constantinople is taken (which in the long run turns out to be a Real Bad Idea. The city is looted, the churches profaned, and the leadership of the crusade is excommunicated a second time.

De Clari wrote that no one knew what happened to the Shroud after the City’s sack, but surely it wound up in someone's baggage.

12. Go West, Old Shroud, Go West!

|

| Chateau de Ray sur Saône manor house of de la Roche |

AD 1349. The cathedral at Besançon was struck by lightning and burnt to the ground. The Shroud likely sustained some scorching, but the poker holes had been made long before, and further fire damage would occur later.

Perhaps fearing for the safety of the Shroud, a copy was painted and when the Shroud of Besançon went on display again three years later in a rebuilt cathedral, it was this copy that was used. Everyone knew it was a painted copy.

Also in 1349, Jeanne de Vergy, a great-great granddaughter of Othon De La Roche, married Geoffrey de Charny. The original Shroud was possibly in her dowry for the excellent reason that from this point on, the provenance of the Shroud is known.

April 10 (or 16). Geoffrey de Charny writes to Pope Clement VI reporting his intention to build a church at Lirey, France. It is said he builds St. Mary of Lirey church to honor the Holy Trinity who answered his prayers for a miraculous escape while a prisoner of the English.

AD 1355. According to the "D'Arcis Memorandum", written more than thirty years later, the first known expositions of the Shroud are held in Lirey at around this time. Large crowds of pilgrims are attracted and special souvenir medallions are struck. A unique surviving specimen can still be found today at the Cluny Museum in Paris. Reportedly, Bishop Henri refused to believe the Shroud could be genuine and ordered the expositions halted. The Shroud was then hidden away.

Since this was roughly when the painted copy went on display at Besançon, it is possible that the Bishop of Troyes confused the two when he famously said that an artist was known to have painted the Shroud.

AD 1356. Sept. 19. De Charny is killed at the Battle of Poitiers, during a last stand in which he valiantly defends his king. Within a month his widow, Jeanne de Vergy, appeals to the Regent of France to pass the financial grants, formerly made to Geoffrey, on to his son, Geoffrey II. This is approved a month later. The Shroud remains in the de Charny family's possession.

AD 1389.

- August 4. A letter signed by King Charles VI of France orders the bailiff of Troyes to seize the Shroud at Lirey and deposit it in another of Troyes' churches pending his further decision about its disposition

- August 15. The bailiff of Troyes reports that on his going to the Lirey church, the dean protested that he did not have the key to the treasury where the Shroud was kept. After a prolonged argument, the bailiff seals the treasury's doors so that the Shroud cannot be spirited away.

- September 5. The king's First Sergeant reports to the bailiff of Troyes that he has informed the dean and canons of the Lirey church that "the cloth was now verbally put into the hands of our lord the king. The decision has also been conveyed to a squire of the de Charny household for conveyance to his master".

- November. Bishop Pierre d'Arcis of Troyes appeals to anti-pope Clement VII at Avignon concerning the exhibiting of the Shroud at Lirey. He describes the cloth as bearing the double imprint of a crucified man and that it is being claimed as the true Shroud in which Jesus' body was wrapped, attracting crowds of pilgrims.

- January 6. Clement VII writes to Bishop d'Arcis, ordering him to keep silent on the Shroud, under threat of excommunication. On the same date Clement writes a letter to Geoffrey II de Charny apparently restating the conditions under which expositions could be allowed. That day he also writes to other relevant individuals, asking them to ensure that his orders are obeyed.

- June. A Papal bull grants new indulgences to those who visit St. Mary of Lirey and its relics.

- June. The widowed Margaret de Charny marries Humbert of Villersexel, Count de la Roche, Lord of St.Hippolyte sur Doubs.

- July 6. Due to danger from marauding bands, the Lirey canons hand over the Shroud to Humbert for safe-keeping. He keeps it in his castle of Montfort near Montbard. Later it is kept at St.Hippolyte sur Doubs, in the chapel called des Buessarts. According to seventeenth century chroniclers annual expositions of the Shroud are held at this time in a meadow on the banks of the river Doubs called the Pré du Seigneur.

AD 1453. March 22. At Geneva, Margaret de Charny receives from Duke Louis I of Savoy the castle of Varambon and revenues of the estate of Miribel near Lyon for 'valuable services'. Those services are thought to have been the bequest of the Shroud, because from now on the Shroud appears in the possession of the House of Savoy.

AD 1457. Margaret de Charny is threatened with excommunication if she does not return the Shroud to the Lirey canons. On 30 May the letter of excommunication is sent.

AD 1459. Margaret de Charny's half-brother Charles de Noyers negotiates compensation to the Lirey canons for their loss of the Shroud, which they specifically recognize they will not now recover. The excommunication is lifted.

AD 1464. February 6. By an accord drawn up in Paris, Duke Louis I of Savoy agrees to pay the Lirey canons an annual rent, to be drawn from the revenues of the castle of Gaillard, near Geneva, as compensation for their loss of the Shroud. (This is the first surviving document to record that the Shroud has become Savoy property) The accord specifically notes that the Shroud had been given to the church of Lirey by Geoffrey de Charny, lord of Savoisy and Lirey, and that it had then been transferred to Duke Louis by Margaret de Charny.

|

| Happy Duke |

AD 1502. Bl. Amadeus IX "the Happy," Duke of Savoy, and his Duchess Yolande of Valois built a ducal chapel for their prized relic, le Saint-Suaire, the Holy Shroud in the cathedral of Chambéry (the capital of Savoy).

AD 1532. A fire at Chambéry damaged the Shroud, creating the major burn marks it presently bears.

Meanwhile, the painting of the Shroud is on display at the Chapel of the Holy Shroud in Saint-Etienne (Besançon). It had become an important object of veneration in the seventeenth century, a period of conflict (Thirty Years War, annexations and withdrawals of France from this region) and yet another round of the plague. Indeed, the surrender of the city in front of the French armed forces, in 1674, was conditioned only upon a requirement to keep this relic at the Cathédrale Saint-Jean de Besançon. When the Revolution came, the Rationalists sent the Shroud of Besançon to Paris (27 Floréal, an II, or May 16, 1794, in real time), where they threw it in a rational fire.

AD 1532. December 4. Fire breaks out in the Sainte Chapelle, Chambéry, seriously damaging all its furnishings and fittings. Because the Shroud is protected by four locks, Canon Philibert Lambert and two Franciscans summon the help of a blacksmith to pry open the grille. By the time they succeed, Marguerite of Austria's Shroud casket/reliquary, made to her orders by Lievin van Latham, has become melted beyond repair by the heat. But the Shroud folded inside is preserved except for being scorched and holed by a drop of molten silver falling on one corner. These are most of the damages now presently seen on the Shroud.

AD 1534. April 16. Chambéry's Poor Clare nuns repair the Shroud, sewing it onto a backing cloth (the Holland cloth), and sewing patches over the unsightliest of the damage. These repairs are completed on 2 May. Covered in cloth of gold, the Shroud is returned to the Savoy castle in Chambéry. These patches, sewings, and re-weavings may well have messed up the sample that was later taken for C14 dating. Depending on how much original and how much patch material wound up in the sample swatches, TOF might intuit a date somewhere close to a weighted mean of c. 400 years old and c. 1900 years old, which is about what they did come up with.

More dates in the modern history can be found here, along with dates in Shroudie history.

Summary

Certainly, a great deal of the reconstruction is speculative and consists of reasonable inferences and filling in the blanks. But it does seem at least plausible that the Shroud of Turin is the Mandylion of Constantinople is the Holy Image of Edessa. But hard data (on just about anything) gets pretty spotty when you get that far back, and you reach an era when records were simply not kept, certainly not in the manner of the modern scientific state. But here is the summary:- Peter takes Shroud to Antioch, where it is hidden away in the Cherubim quarter against discovery by Jews and Romans.

- During reign of Commodus, it is taken to Edessa to "seal the deal" with Lucius Agbar. (God says to him, "Luke, I am your Father that art in heaven." ROFLOL!) The story is eventually projected onto an earlier time period.

- Becomes dangerous once more to show your head. Shroud is hidden, forgotten, until flood or earthquake opens its hiding place in the wall of the Cherubim Gate. The district becomes known for its special icon.

- When Persians destroy Antioch, the Shroud is moved to Edessa, where it plays a folkloric role in foiling a Persian siege. Folded up and kept in a box, it becomes the famous Image of Edessa.

- The Roman Emperor decides the Image belongs in the City and the Image is taken to Constantinople, where it becomes known as the Holy Mandylion. Gradually, people seem to become aware there is a full body, and it begins to be associated with the burial shroud of Christ.

- Othon de la Roche takes the Shroud to Athens as part of his booty from the Sack of Constantinople and then sends it to Besançon.

- Othon's great-great granddaughter Jeanne inherits and she and her husband Geoffrey de Charny house the Shroud at Lirey. (A painting replaces it at Besançon and is eventually destroyed by the French in a Revolutionary hissy fit.)

- Margaret de Charny pulls the Shroud from Lirey and puts it in Montfort for safekeeping. The Livey monks never get it back.

- Margaret turns the Shroud over to the House of Savoy, who keep it first at Chambéry (where it is damaged in a fire) then at Turin (where it remains to this day).

References

Shroudie sites should be taken with a grain of salt, since they often over-state the case established by the facts and make more out of something than the evidence will actually bear. The same is true of skeptical sites, but in the opposite direction, often finding good reasons to reject each piece of evidence, but not considering that they must explain pretty many pieces. With that in mind, three sites with linkages to much else are:

1. Great Shroud of Turin. This has a great many mini-articles that both support or debunk various claims about the shroud. This link is to the FAQ page, which will give access to all the rest. The site-master believes the shroud is genuine, and claims to be an Episcopalian.

2. Bible Archeology contains a number of disparate articles, which TOF has not looked at, but includes several on the Shroud, esp. on its history. The site is run by deep fundamentalists, who consider "the accounts found in Genesis 1-11 to be factual historical events," and therefore needs to be weighed carefully wrt the first site. It is less critical of the evidences than the first site, but contains syntheses of the history:

- The Shroud of Turin's Earlier History: Part One: To Edessa

- The Shroud of Turin's Earlier History: Part Two: To the Great City

- The Shroud of Turin's Earlier History: Part Three: The Shroud of Constantinople

- Latest Developments on the Shroud of Turin: Part I

- Latest Developments on the Shroud of Turin: Part II

- He has a host of photographs from STURP, in particular the sequence starting with 5-C-10 as well as others further down the scroll.

- He also includes a roster of scientific articles and papers.

- and an extensive chronology from the 1300s to the 2000s

Fascinating!

ReplyDeleteAt a monastery near my town, the Dominican nuns have a 400-year-old replica of the Shroud on display in the Church. "This Shroud replica was commissioned by the Most Serene Infanta, Maria Maddalena of Austria, Grand Duchess of Tuscany, wife of Cosimo de’ Medici in April, 1624. To give the copy greater value it was placed for a time on the Shroud of Turin" (http://nunsopsummit.org/history/copy-of-the-shroud-of-turin). It is striking to me that even a "modern" copy is centuries old, older than my country!

Touching something to a relic makes the touching thing itself a third-class relic, IIRC. Which is why a lot of people go around touching handkerchiefs (very Acts of the Apostles) or rosaries to relics.

DeleteSo yeah, a Shroud painting is nice, but a Shroud painting that's a third-class relic is nicer.

Also interesting to me:

ReplyDeleteso... you are a writer of (science?) fiction who is also a statistics guy (was that your original line of work?) who also knows piles of detailed information about Late Antiquity and the Medieval period?

I was a quality engineer, statistician, and consultant in quality management. (The first and third will be clear once you realize that "quality" is a noun.) I wrote science fiction as a hobby, and then began to sell. I was always interested in history, but got deeper into the world of late classical and medieval Europe while researching the SF novel Eifelheim.

DeleteExcellent, excellent! I love the wide-ranging topics on this blog. I look forward to reading Eifelheim.

DeleteI wonder if anyone will ever try DNA tests on the shroud.

ReplyDeleteIt seems more likely that one or more of the women would have been the ones to first retrieve and store the linen. This would explain, also, why no mention of it is made in the Gospels or Acts.

ReplyDeleteMy initial guess would of course be the BVM. But, given her age and emotional state at the time, I would lean toward Magdelene or one of the others, who might have at first kept it either for personal sentimental reasons or out of practicality (linen, I imagine, was not cheap- and there would certainly be others to bury).

The article is fine as it stands, but seems to be a word for word plagiarism from two authors, Jack Markwardt and Daniel Scavone without proper attribution being given. Jack Markwardt - "Antioch and the Shroud" (Dallas Conference 1998) & "ANCIENT EDESSA AND THE SHROUD: HISTORY CONCEALED BY THE DISCIPLINE OF THE SECRET" (Ohio Conference 2008); Daniel Scavone - "BESANÇON AND OTHER HYPOTHESES FOR THE

ReplyDeleteMISSING YEARS: THE SHROUD FROM 1200 TO 1400" (Ohio Conference 2008). Comment by daveb of wellington nz.

There was an essay by Markwardt regarding Antioch on one of the sites that were linked at the end. I have not read either of the others, and 'disciple of the secret' sounds a little danbrownish for me.

DeleteAin't danbrownish. Concerns well-known "Disciplina arcana", pre-Constantine Christian code to keep secrets from persecutors. Follows Christ's advice "Cast not your pearls before swine!" E.g. "Ichthus" = "Fish" = Jesus; there's a lot more. Markwardt uses it to decrypt early subtext references to the Shroud, somewhat along lines of "Hymn of the Pearl". Strange you say you haven't read it. Seems 'word for word' from his paper, including his references. daveb of wellington nz

DeleteCould be that it was used on one of the sites I visited, because I do remember looking up several translations of the "Hymn of the Pearl" and not finding any that corresponded to the claimed Shroud relationship. Everyone knows about the fish. We were taught that in school.

DeleteMarkwardt's 2008 paper, developing his 1998 still further can be found at: http://ohioshroudconference.com/papers/p02.pdf

ReplyDeleteYou'll see there his attempts to penetrate "disciplina arcana" which is useful in supporting some of the ideas in your article. He also refers to the "Hymn of the Pearl", maybe one you're looking for. Dr Brian Colless of NZ is a foremost authority on Hymn of Pearl. You can get to his versions and interpretations starting at https://sites.google.com/site/collesseum/

but all interpretations of Pearl seem couched in controversy!

Jack Markwardt tells me he is planning another paper on reconstruction of the early history, to be presented at forthcoming Shroud Conference. Suggest you watch out for it. Best! daveb of wellington nz

This article is amazing...

ReplyDelete