|

| Tristan and Iseult |

A Novel Idea

Among the gifts of the Middle Ages was the roman of the langue d'oil. Stories like Tristan and Iseult were different from the chansons de geste of the langue d'oc. Those had featured stereotypes -- brave hero, cowardly traitor, et al. -- performing iconic deeds symbolizing eternal verities. Not only were the chansons symbolic; symbolism was very nearly the point of it all.

|

| The knight pledges fealty to... a woman? The seal of Raymond de Mondragon posted by Gilles Dubois |

All of literature as we know it -- we might even say all of humanism -- stems from this idea of the character-who-changes through a series of events and encounters. But it all hinges on the notion that there actually are interior conflicts, psychological situations, and the like. It hinges, in short, on the freedom of the will.

Where There's a Way, There's a Will

Eliminative Materialism raised its pointy head in the 1960s to argue that there were no intentions, no beliefs, no ideas, but only the wind of physical causation blowing through the neural branches of the brain to create meaningless outputs. Although it is silly tout court, it has been passed along in one form or another like a venereal infection, often with the breathless aspect of one who believes he has discovered it for the first time. Or at least it's what all the kids at the Kool Kids' table say. Many do not follow the logic of it all the way down to the bone as the Churchlands and others have done, but think they can pull one brick out of the house without the whole wall weakening and collapsing on top of them.

Yes, that's right, sports fans! They're off the reservation, anxious to provide A.N. Whitehead with that "curious object of study."

It is deja vu all over again, as the great Yogi Berra once said. Once more it is amateur hour in the theater of philosophy. Trailing in the footsteps of Sam Harris, Patrick Haggard, and others, a congeries of atoms self-labeled for convenience "Jerry Coyne" was impelled by forces inevitably entailed by the Big Bang to output an editorial in USA Today, proving once again that those obsessed with religion wind up trashing humanism in their iconoclastic zeal:

He reveals three conclusions of his thesis.

- The will is not "free.

- There is no "will."

And, when he writes: "we" are simply constructs of our brain, - There is no "you."

But wait! "We" are simply constructs of our brain? Whose brain?

The Definition

The first error comes early, when inputs compel the coynean brain-atoms to output this string:

But before I explain this, let me define what I mean by "free will."

Question: How hard can it be to deconstruct a proposition when you get to define the terms?

Answer: Not nearly as hard as it would be if one used the actual definitions employed by the people who developed the concept in the first place.

That the definition the coynean atoms were compelled to use is "simply ... the way most people think of it" is little help, since "most people" are unlikely to have thought about it at all, let alone to have thought about it rigorously and logically. What if someone were to deconstruct evolution, saying "Let me define what I mean by 'evolution.' I mean it simply as the way most people think of it" and then go on to give some popular but simplistic misconception? No one as well-versed in the science of evolution as the redoubtable Jerry Coyne would be (were he not simply a construct of his brain) would accept such amateurishness for an instant. Nor should he do so when it is in a field wherein he is the amateur.

Here is the definition of free will emitted by the coyne brain-atoms (Hold onto your hats):

When faced with two or more alternatives, it's your ability to freely

and consciously choose one, either on the spot or after some deliberation.

and consciously choose one, either on the spot or after some deliberation.

| A simple curve |

| A non-simple, or complex curve |

So what is the traditional definition of liberum arbitrium? It's ground we've covered before; but we'll repeat it down below. It's not like the coyne atoms are breaking new ground here.

A Test of Free Will

The brain atoms then propose:

A practical test of free will would be this: If you were put in the same position twice

— if the tape of your life could be rewound to the exact moment when you made a decision,

with every circumstance leading up to that moment the same and all the molecules

in the universe aligned in the same way — you could have chosen differently.

— if the tape of your life could be rewound to the exact moment when you made a decision,

with every circumstance leading up to that moment the same and all the molecules

in the universe aligned in the same way — you could have chosen differently.

If this is the coynean brain-atoms' notion of a practical test, one wonders what would constitute an impractical one. But this sort of thing seems to be the norm among those whose brains practice philosophy without a license. We cannot in practice rerun the tape.

|

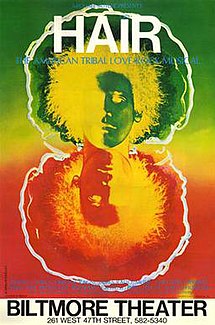

| This is the dawning of the age of Aquarius, or the new Mayan calendar or something |

On the other hand, the less-superstitious Stephen J. Gould famously asserted that were the clock of evolution reset, totally different species would likely evolve than those we know. Apparently, natural selection has free will, but we don't.

John Adams once observed that atheists generally belong to one of two sects. One ascribes everything to Fate (determinism). The other ascribes everything to Chance (randomness). Clearly, the coynean brain-atoms belong to the former sect, while the late Dr. Gould belonged to the latter. The curious thing is that devotees of each sect will wave their own metaphysical banner as proof that theism is wrong. It is wrong because everything is deterministic and nothing is due to chance. Or it is wrong because everything is random and nothing is determined. What this really indicates is that the truth or falsity of theism is entirely independent of whether Newton or Schrödinger wins the smack-down.

|

| Coynean free will |

The Argument from Determinism

Unable actually to rewind the tape, thus making the "practical experiment" completely nugatory, the coynean brain-atoms then provide "two lines of evidence" to suggest that such free will is an illusion. They are the same lines as in the 1960s when this sort of thing began.

we are biological creatures, collections of molecules that must obey the laws of physics.

All the success of science rests on the regularity of those laws,

which determine the behavior of every molecule in the universe.

All the success of science rests on the regularity of those laws,

which determine the behavior of every molecule in the universe.

|

| Uncertain who this is? |

|

| A crashing Bohr |

The proposition that {The world is lawful} is not the same as {The world is deterministic}.

Back when aqueducts were the cutting edge of technology, people saw the world in hydraulic metaphors and gave us the scientific theory of humors. So in the Machine Age, it was only natural to view nature as a collection of machines. But that some aspects of nature can be imitated by a machine does not entail that nature is a machine. We must not confuse a useful poetic metaphor for an ontological reality.

|

| Your secret master |

The Argument From the Brain

When the coynean brain-atoms emit "your brain — the organ that does the 'choosing,'" a second palmed ace is revealed. Namely, the assumption that an organ is an actor. We might say "your hand — the organ that does the 'grasping.'" There is some truth to it, but try saying "your hammer — the tool that does the 'nailing.'" Like the hand and the brain, the hammer does nothing unless someone uses it. In particular, no organ acts as an organ apart from an organism. Try putting a brain in a vat and see how long it takes before it constructs a "me." It is the whole being that exercises emergent properties, not any of its parts. The situation is complicated by people who live normal lives despite having very little brain. The condition is called Dandy Walker complex and is a genetically sporadic disorder that occurs in one out of every 25,000 live births. There have been enough such cases that Dr. John Lorber published a 1980 article in Science titled "Is the Brain Really Necessary?" People born with parts of their brain missing will sometimes recruit other parts of their brain to perform the functions of the missing portions. This again suggests that the brain is in the self, not the self in the brain.

Chase Britton: Boy Without a Cerebellum Baffles Doctors

Consciousness in congenitally decorticate children: developmental vegetative state as self-fulfilling prophecy

(h/t to the Codgitator and Joseph for these examples)

We can't impose a nebulous "will" on the inputs to our brain that can affect

its output of decisions and actions, any more than a programmed

computer can somehow reach inside itself and change its program.

its output of decisions and actions, any more than a programmed

computer can somehow reach inside itself and change its program.

What it means to "impose" a will (nebulous or otherwise) on the "inputs" is unclear. Is it nebulous to "impose" a nebulous gravity on a planet? Gravity, like the will, is not separable from the physical body, but is itself not a material entity. Gravity, reproduction, motion, will are just examples of powers various kinds of material bodies possess: inanimate, vegetative, animal, and rational. Consider the problem of intention. How can you look at something?

The "inputs" to the brain are the sensations. At every moment, the senses are inundated with a cascade of photons, air waves, odor molecules, and so forth. Take photons. Where I sit right now, my eyes are awash in photons bouncing off the computer screen, the tea cup next to it, an empty can of Dr. Pepper Diet Caffeine Free, a Roget's Thesaurus, a cell phone, a talking bobble-head doll of Albert Einstein, a bust of Beethoven, the back wall for the desk, pigeon holes with CDs, manila folders, and so on. In terms of "inputs" all of these are going into my brain. So how is it that what I "see" is the tea cup? Somehow I can seine the whirlwind of otherwise meaningless photons and "privilege" those that have bounced off the tea cup. IOW, I really am able to "impose" my will on the inputs. Because there is nothing in the photons that can account for this. And this involves only the sensory imagination, not even the rational faculties.This matter is discussed more fully in "Nonlinear Brain Dynamics and Intention According to Aquinas," by Walter J. Freeman, Dept. of Molecular and Cell Biology, U Cal Berkeley, Mind & Matter Vol. 6(2), pp. 207-234

And that's what neurobiology is telling us: Our brains are simply meat computers

that, like real computers, are programmed by our genes and experiences

to convert an array of inputs into a predetermined output.

that, like real computers, are programmed by our genes and experiences

to convert an array of inputs into a predetermined output.

(Yup, he wrote that real computers are programmed by our genes. However, TOF will ascribe that to poor command of English grammar rather than to bizarre metaphysics.) But are our brains "computers"? See Minds, Machines and Gödel, J.R. Lucas

As Searle has pointed out, there are no computers in material nature. There is only plastic and metal and such. What makes it a computer are the intentions of a user. My tea cup, aforementioned, is a computer, presently executing the program "Sit there and hold my hot decaff tea." You see, just as the ancients saw hydraulic models everywhere in nature, and the moderns saw mechanical models everywhere in nature, we post-moderns now see computers everywhere in nature. The brain is now metaphorically a computer rather than a machine or a mixing bowl for the humors. But a poetic analogy is not necessarily an equivalence.

Is the Brain a Digital Computer? John R. Searle

Words like "computer," "programming," "code" and so forth inherently point to something outside the brain; that is, they are teleological. How can genes "program" a brain when genes have no intention? In a series of causal connections

→X→X→A→B→X→X→X→

where A represents the age of the tree and B represents the number of rings, what privileges A and B as the two end-points of a scientific law? What makes A the cause and B the effect when there are a host of Xs that come before A and after B? Answer: intention. But if the human mind has no will, it has no intention, and so there are no scientific laws, only material concatenations.

Recent experiments involving brain scans show that when a subject "decides" to push

a button on the left or right side of a computer, the choice can be predicted by brain

activity at least seven seconds before the subject is consciously aware of having made it.

a button on the left or right side of a computer, the choice can be predicted by brain

activity at least seven seconds before the subject is consciously aware of having made it.

We've seen this "experiment" before. Who ever supposed that a free exercise of will could not be predicted? The "can be predicted" meant that 60% of the time the prediction was correct. I could almost match that with a coin toss. From a materialistic viewpoint, all that has been observed is a flow of blood in certain regions of the brain "associated with" a motor function. It was the experimenter's free will intention to call that a "moment of decision." However, an article in Nature tells us:

Das and Sirotin used electrodes to measure neuronal activity at the same time and place as blood flow in monkeys who were looking at an appearing and disappearing dot. As expected, when vision neurons detected the dot and fired, blood rushed into the scrutinized brain region. But surprisingly, at times when the dot never appeared and the neurons remained silent, the researchers also saw a dramatic change in blood flow. This unprompted change in blood flow occurred when the monkeys were anticipating the dot, the researchers found. The imperfect correlations between blood flow and neural firing can confound BOLD signals and muddle the resulting conclusions about brain activity.So what the experiment showed is that the subjects body, habituated to a routine task, anticipated that task by as much as a few seconds.

"Brain imaging measures more than we think: Anticipatory brain mechanism may be complicating MRI studies," Nature (21 Jan 2009)

"Decisions" made like that aren't conscious ones. And if our choices are unconscious, with some determined well before the moment we think

we've made them, then we don't have free will in any meaningful sense.

we've made them, then we don't have free will in any meaningful sense.

Of course, it means nothing of the sort. Bodily anticipation of a known muscle motion is not a "decision."

The traditional philosopher will quite happily acknowledge that some decisions really are automatic, unconscious, habitual, genetic, impaired by strong drink, and so on. (Aquinas gives the example of a scholar absent-mindedly stroking his beard. So it's not like these are brand new ideas.) Most of life is lived on automatic pilot. No problem.

Oh Noes! What to Do?

The most bizarre part of the column is that after telling us we have no free will, the coynean brain-atoms then tell us

So if we don't have free will, what can we do?

Well, according to the rest of the column, there is nothing that "we" can "do," because "we" is an illusion and so is the choice to "do" anything. We will simply be blown hither and yon by the winds of Newtonian physics.

And there are two upsides [to denying free will]. The first is realizing the great wonder and mystery of our evolved brains, and contemplating the notion that things like consciousness, free choice, and even the idea of "me" are but convincing illusions fashioned by natural selection.

If "me" is an illusion, it is difficult to figure exactly who will be realizing, wondering, and contemplating - or suffering the illusion. If there is no free will, then whether the illusion of "we" suffers the illusion of wonder will be the result of physics and not a consequence of the denial, let alone an upside. But that's sort of incoherence is what happens when you arbitrarily change one piece in the jigsaw puzzle of life. The rest starts to not fit together right.

Further, by losing free will we gain empathy, for we realize that in the end all of us, whether Bernie Madoffs or Nelson Mandelas, are victims of circumstance — of the genes we're bequeathed and the environments we encounter. With that under our belts, we can go about building a kinder world.

In other words, the brain atoms have discovered that we are all sinners and "there but for the grace of God go I." How "losing free will" will necessarily generate the illusion of empathy is left unsaid; as are the reasons this would impel "us" to build a "kinder" world. Can't "go about" doing diddly without first deciding to do it, and ex hypothesi, there ain't no deciding going on. So whether a kinder world gets built is a consequence of the alignment of molecules in the universe, not of any illusory realization by an illusory "we."

So What is Liberum Arbitrium?

philosophers have concocted ingenious rationalizations for why we nevertheless

have free will of a sort. It's all based on redefining "free will" to mean something else.

have free will of a sort. It's all based on redefining "free will" to mean something else.

Of course, the perceptive reader will have noted how clever the philosophers were to have "re"-defined free will so many centuries before the winds of random causes blew through the coyne-atoms to output that random string. Or could it be the coyne-atoms that have redefined free will using a tautologous definition? What we shall do is remind our Gentle Reader of the original definition of liberum arbitrium, the one that lay behind all that philosophizing and theologicizing that so many are anxious to avoid.

First, the will.

As the diagram indicates, the Volition stands to the Intellect (Conception) as the Emotions stand to the Imagination (Perception). So the will is a kind of appetite or desire; viz., the intellective appetite, analogous to the sensory appetites. It is a "hunger" or "desire" for abstracted concepts. This is one of the reasons that "experiments" in which the subjects twitch fingers or flip switches aren't testing the Will as such. Bodily motions are not the proper object of volition (except to the extent that the intellective appetite may govern the sensitive appetites, cf. dieting.)

Proof that the Will is Free

1. It is impossible to desire what you do not know.

2. Our knowledge of an end may be imperfect.

3. Therefore, our desires toward it are imperfectly determined.

4. That which is imperfectly determined is free to some degree or another.

We can test this by considering a case in which knowledge is perfect. For example, that 2+2=4 is to one versed in arithmetic perfectly known. The will has then no latitude (degrees of freedom) in "choosing"/"assenting to" it. If however, we were given the proposition "Card X = card Y iff א(X) = א(Y)" the will would be free to assent or withhold assent to the extent that one had knowledge or not of cardinal arithmetic. IOW, "free" is not meant in the Nietzschean sense (the triumph of the Will over the Intellect), but in the Aristotelian-Thomistic sense by which the Intellect is prior to the Will.

The will's freedom follows from the quality of the information it receives from the intellect. The fuzzier the knowledge, the freer the will. But inasmuch as nothing in the physical world is as perfectly known as in mathematics, the will has "play" or "freedom" in virtually all circumstances. It may help to understand "free" will in the same sense as "free" fall or a "free"-running river.

The interested reader may refer to

Thomistic Psychology, Robert E. Brennan

Philosophy of Mind, Edward Feser

As well as two short blog posts:Ramble on free will, James Chastek

A thought experiment about determinism, James Chastek

Umm, Didn't We Get Off-Target?

Not really. The coyne-atoms took aim at a no doubt sincerely held illusion that free will was "religiose" and therefore double-plus ungood. Because of this, free will is double-plus ungood, and rejected. Otherwise, the grave insistence with which people insist that they do not exist, cannot think, cannot intend, etc. is incomprehensible. But in taking aim at religion, they popped humanism square between the eyes.Because literature not only makes no sense if eliminative materialism is true, the whole rationale of the roman becomes vacuous. And we note in passing that many in that camp - at least on the Internet - seem to have a tin ear for literature and the literary way of thinking. Did not Hume, after all, recommend burning all such books?

"The man who begins to think without the proper first principles goes mad; he begins to think at the wrong end. And for the rest of these pages we have to try and discover what is the right end. But we may ask in conclusion, if this be what drives men mad, what is it that keeps them sane? By the end of this book I hope to give a definite, some will think a far too definite, answer. But for the moment it is possible in the same solely practical manner to give a general answer touching what in actual human history keeps men sane. Mysticism keeps men sane. As long as you have mystery you have health; when you destroy mystery you create morbidity. The ordinary man has always been sane because the ordinary man has always been a mystic. He has permitted the twilight. He has always had one foot in earth and the other in fairyland. He has always left himself free to doubt his gods; but (unlike the agnostic of to-day) free also to believe in them. He has always cared more for truth than for consistency. If he saw two truths that seemed to contradict each other, he would take the two truths and the contradiction along with them. His spiritual sight is stereoscopic, like his physical sight: he sees two different pictures at once and yet sees all the better for that. Thus he has always believed that there was such a thing as fate, but such a thing as free will also. Thus he believed that children were indeed the kingdom of heaven, but nevertheless ought to be obedient to the kingdom of earth. He admired youth because it was young and age because it was not. It is exactly this balance of apparent contradictions that has been the whole buoyancy of the healthy man. The whole secret of mysticism is this: that man can understand everything by the help of what he does not understand. The morbid logician seeks to make everything lucid, and succeeds in making everything mysterious. The mystic allows one thing to be mysterious, and everything else becomes lucid. The determinist makes the theory of causation quite clear, and then finds that he cannot say "if you please" to the housemaid. The Christian permits free will to remain a sacred mystery; but because of this his relations with the housemaid become of a sparkling and crystal clearness. He puts the seed of dogma in a central darkness; but it branches forth in all directions with abounding natural health."

ReplyDeleteClearly the free-will-despisers are not new: Chesterton thus refutes them over a hundred years ago.

Some foolish (or dishonest) 'atheists' imagine they can mock me when I argue that "You/I do not exist" is *precisely* the logical entailment of "God does not exist".

ReplyDeletePutting aside the nonsensical things and blatant, self-destroying contradictions in his op-ed, I'd question the nature and means of reaching this "kinder world". He seems to start to address the justice of punishing an ugly bag of mostly water who does not exist as a conscious entity but has violated some meaningless construct imposed by other selfless water-bags. But he doesn't do a very good job of it. What is this "justice" anyway? What atoms is it composed of? In what sense can one who is not an "I" choose for or against this Justice Particle?

ReplyDeleteI think the monstrous end of this fuzzy road of thinking is rule by brute force. Since the Other cannot control his choice any more than I can, why should I try to convince him or influence him? Why not just impose my non-will on him? He's nothing special, after all...just a bag of water. And indeed, those who are predisposed by their programmer Genes to think and do ungood things should certainly be prevented from passing on those Genes. There is nothing sacred or praiseworthy about them...they are merely meat machines like everything else.

Reading this post, this Chesterton quote from Heretics came to mind :-)

ReplyDelete"When Thomas Aquinas asserted the spiritual liberty of man, he created all the bad novels in the circulating libraries."

Since we've had discussions on this topic over at John C. Wright's blog, and since I just posted The No Free Will Theorem on my blog, and since Fighter07 directed me to your post, I thought I'd stir the pot. I offered a brief comment to your post in my reply to Fighter07.

ReplyDeleteMany [eliminative materialists] do not follow the logic of it all the way down to the bone as the Churchlands and others have done, but think they can pull one brick out of the house without the whole wall weakening and collapsing on top of them.

ReplyDeleteMy favorite part of eliminativist nonsense is that not only are the self, beliefs, thoughts, etc, illegitimate concepts that are to be superseded by more "scientific" concepts (or more "scientific" whatever-is-supposed-to-replace-concepts), but *true* and *false* are *also* illegitimate concepts, since those are properties that beliefs have, and beliefs don't exist according to this model. So the eliminativist can't even say that your position is false and their is true. They can only say that their position is some non-concept that hasn't even been non-thought of yet, which is totally meaningless.

The "nonreductive materialists" and "mind-brain" identity theorists are no better, of course - they being nothing more than eliminativists with an equivocation problem. The best they can do is take some hypothetical physical behavioral property, which they can't even identify (but promise to do in the future!), and *call* it "truth". This, of course, is essentially the same as saying that notions of true and false will be replaced by successor concepts in the future, and hence literally isn't even wrong by its own reckoning.

So free will is defined as "your ability to freely... choose." Well, that's useful.

Of course, what Coyne is *actually* trying to get at is the notion that we don't ever actually make decisions for logical reasons, based on chains of rational inference, but that all we do is actually determined by factors that are fully predictable mathematically, rendering our reasons and our logical reasoning epiphenomenal (or nonexistent actually, since there's not even an "us" to have the reasons).

If "me" is an illusion, it is difficult to figure exactly who will be realizing, wondering, and contemplating - or suffering the illusion.

The claim that consciousness and/or selves are illusions is my favorite piece of incoherence by "folk" eliminativists like Coyne. The "professional" eliminativists (and yes, I realize that this is something like professional schizophrenia, hence the scare quotes) like the Churchlands usually try to avoid stating such immediately obvious contradictions as that the self is illusion (experienced by its illusory self!), or that consciousness is an illusion (being consciously experienced illusorily!).

In other words, the brain atoms have discovered that we are all sinners and "there but for the grace of God go I."

In other words, right after saying that rational inference doesn't really exist, and that none of our behavior can be caused by it, Coyne goes on to predict that the rational inference that determinism logically implies an inability to control one's actions will cause us to behave more empathetically.

Of course, what Coyne is *actually* trying to get at is the notion that we don't ever actually make decisions for logical reasons, based on chains of rational inference, but that all we do is actually determined by factors that are fully predictable mathematically, rendering our reasons and our logical reasoning epiphenomenal (or nonexistent actually, since there's not even an "us" to have the reasons).

Delete"Logical reasons, based on chains of rational inference" is not opposed to "factors that are fully predictable mathematically". One can use math to describe how the circuits in a computer work; one can also use math to describe the algorithms executed by the computer. Physics is described by math. Software is described by math. One could describe software using the math of physics, but it's darn inconvenient. We abstract it at a different, higher level. But it's language all the way down.

Honestly, other than the first sentence, I'm not sure how to read what you just said as anything but a change of subject. And btw, you couldn't describe software using only the math of physics, even though software is deterministic (I'll leave it to you to try and figure out why).

DeleteOf course we can describe software using the math of physics. The computer, which contains the software, is a physical object. The memory that store the bits, whether instructions or data; the gates that fetch, decode, and execute instructions, and the electrons that flow through the gates are all physical objects, and therefore describable by the math of physics. So if you're going to argue otherwise, it's incumbent on you to explain why. I'm guessing that perhaps you might try to state that software is machine independent and therefore exists apart from the machine on which it executes (a Platonic universal, as it were), but this assumes that Plato was right. But he isn't -- software doesn't exist in this universe apart from a physical medium, whether it's the human brain or electronic mind. But even were I to grant you this assumption, all software can be embedded in some machine; and that entire system is describable by physics.

DeleteI'm guessing that perhaps you might try to state that software is machine independent and therefore exists apart from the machine on which it executes

DeleteNope, keep guessing. Though you have introduced a separate problem for your view here which you haven't dispensed with: namely that the same software running on different machines, stored on different types of storage media, or even two instances of the software running on the same machine, would all be physically different. So you couldn't give a physical description of the software per se, but only of the electromagnetic events and states comprising a individual executions or stored instances of the software. Nothing in the physical description would identify all the different sets of physically different events as being the same software. Additionally, nothing in a physical description of a single stored or executing instance of the software would distinguish the electromagnetic states or events comprising one instance of the software as being a separate piece of software from all the other electromagnetic states or events occurring in the storage medium or CPU.

And, finally, there's a couple more points I wanted to make on this topic.

DeleteThe first is that mathematical reasoning is a particular type of rational reasoning. Math derives, at least in part, from logic. Mathematical proof is built on and requires the same laws of logic (identity, non-contradiction, modus ponens, etc) as rational argument in general does, and mathematical equations are therefore premised in the laws of logic for their meaning and coherence. The rules of logic, therefore, cannot be reduced to or described by math (whether math reduces to logic is a question of serious continuing debate).

Secondly, material things don't actually engage in mathematical reasoning anyhow, much less logical reasoning more generally. Rather, they behave in ways that can be approximated by or modeled with mathematical equations by those of us who do engage in mathematical reasoning.

Consider the case where I conclude that it is impossible for any two-dimensional shape to be both a square and triangle at the same time. This is a rational conclusion, because I have grasped the logical relationship between the propositions "This 2-dimensional shape is a square" and "This 2-dimensional shape is a triangle" and perceived that they stand in contradiction to each other. Moreover, this logical relationship is universal. I know, with logical certainty, that the impossibility of square triangles is not only true for me, but for all people, in all times and places, both future and past, that it was true before there were any people, and that it's even true in any parallel universes (if there are such things, which I don't believe).

In order for my conclusion to be rational, it is necessary that it is caused by me having grasped the logical relationship between squares and triangles, and having perceived that the relationship is one of contradiction. And that means that the universal logical relationship *itself* must have been part of what caused my conclusion, such that my saying that square triangles are impossible cannot be adequately accounted for without mentioning that the universal logical relationship caused me to do it.

But if my actions are entirely caused by and can be entirely accounted for by material events, then this is not the case. All material causes are particular. No set of material entities or causes (which exist in a particular state at a particular time and place) can literally *be* a universal logical relationship that applies to everyone and everything at all times and all possible universes. If my conclusions are entirely determined by material causes, then, it means that they are in no way determined by the logical relationship and my perception of it (in fact, it means that there's no "me" to even rationally perceive it!), and that they are therefore non-rational.

Some more on this issue (and others) from Ed Feser: http://edwardfeser.blogspot.com/2010/08/fodors-trinity.html

Nope, keep guessing.

DeleteI don't care to play that game. I will address any objections you care to raise, but I'm not a mind reader.

Though you have introduced a separate problem for your view here which you haven't dispensed with: namely that the same software running on different machines, stored on different types of storage media, or even two instances of the software running on the same machine, would all be physically different.

That's not a problem. When I designed my first adder, I think I used 27 NAND gates. I have a friend who designs hardware for a living and he did it in 10 gates. I then managed to do it in 9. So this shows three different physical systems that give the same result. It's the result that matters, not the implementation.

So you couldn't give a physical description of the software per se, but only of the electromagnetic events and states comprising a individual executions or stored instances of the software.

A physical description of all of the executable paths of the software is the software. And a physical description has to be possible, because a running computer is a physical object.

Additionally, nothing in a physical description of a single stored or executing instance of the software would distinguish the electromagnetic states or events comprising one instance of the software as being a separate piece of software from all the other electromagnetic states or events occurring in the storage medium or CPU.

So what? The entire system is what we're interested in. That's what thinks.

The rules of logic, therefore, cannot be reduced to or described by math (whether math reduces to logic is a question of serious continuing debate).

DeleteThat's demonstrably not true. There are any number of theorem provers that "reduce" the laws of logic to software. Per our previous discussion, software can be described via the equations of physics. The "rules of logic" are identical to matter in motion in certain patterns.

Secondly, material things don't actually engage in mathematical reasoning anyhow, much less logical reasoning more generally.

Sure they do. We have programs that can use their camera to view scenes, determine what is in the scene, and answer questions about the scene.

Rather, they behave in ways that can be approximated by or modeled with mathematical equations by those of us who do engage in mathematical reasoning.

And our mathematical reasoning follows the laws of physics. Too, the simulation/approximation/model of intelligence is intelligent (for suitably close simulations).

But if my actions are entirely caused by and can be entirely accounted for by material events, then this is not the case.

Tell that to the researchers who were surprised when their geometric theorem prover came up with an elegant proof for a certain theorem about triangles.

No set of material entities or causes (which exist in a particular state at a particular time and place) can literally *be* a universal logical relationship that applies to everyone and everything at all times and all possible universes.

Perhaps you're stuck in some kind of weird Platonic universe where "universals" exist apart from matter. They don't. What your brain has done is set up an isomorphism between two things, where one (or both) of those things is a mental abstraction. It's all software. But software, and mental abstractions, are just another form of matter in motion.

When I designed my first adder, I think I used 27 NAND gates. I have a friend who designs hardware for a living and he did it in 10 gates. I then managed to do it in 9. So this shows three different physical systems that give the same result.

DeleteActually, if we go by your reasoning, they each gave completely different results. After all, each result was a different material entity. Different electrons, different times, different machines. Now, maybe you're trying to tell me that they were the same result in that they all exhibited the same abstract pattern and symbolized the same universa- oh wait, that can't be what you mean.

A physical description of all of the executable paths of the software is the software.

A physical description of something *is* the thing? So, like, if I look up "cat" in an encyclopedia, the description contained therein actually *is* a cat, provided it's thorough enough? And I'm some kind of voodoo-practicing Platonist?

And what's this about all possible "executable" paths of an executing program being the program? "Possible" paths that don't actually get executed are mere abstractions, and that means that they don't exist at all (according to you as of five minutes ago), you filthy Platonist you!

We have programs that can use their camera to view scenes, determine what is in the scene, and answer questions about the scene.

And we've had abacuses that do math for centuries! How silly I was to think otherwise!

There are any number of theorem provers that "reduce" the laws of logic to software.

Please tell me that you're not trying to cite programs like LogicCoach as proof that logic reduces to math (That's rhetorical, I'm actually quite sure that that's exactly what you're doing).

Then again, this will make arguing a lot easier for me. All I've got to do is come up with a program where Affirming The Consequent and Denying The Antecedent are counted as valid forms of argument. In fact, I think I'll change my brain-software to think that starting... now! Nobody can tell me that I'm wrong, or that I'm just embarrassing myself by committing elementary fallacies unbecoming a toddler with my "fake", "subjective," "made-up" laws that violate the so-called "objective," "universal," "real" laws of logic! There are no universal laws of logic! I am my own God, mwahhahahahaHA!

Congrats, wrf3, I've come around to your position. Or... I guess a different position, because we can't literally share the *same* position, because our brains are different material entities in different places and there are no abstract universals that we could actually share. Ah, what the hell, I'll just get rid of my own personal Law Of Non-Contradiction while I'm at it and come around to your position anyhow! And... DONE!

42 is the meaning of life, because pi is the most delicious flavor of Christopher Columbus!

Perhaps you're stuck in some kind of weird Platonic universe where "universals" exist apart from matter.

I hate to belabor the obvious, but since no chunk of matter is universal, universals either exist apart from matter or not at all. Oh crap, disregard that. That was the old non-me talking.

Actually, if we go by your reasoning, they each gave completely different results.

DeleteNo, they had two different physical descriptions that gave the same results.

Now, maybe you're trying to tell me that they were the same result in that they all exhibited the same abstract pattern and symbolized the same universa- oh wait, that can't be what you mean.

No, the "abstract pattern" (I assume you mean the physical equations) are different. But they do symbolize the same universal -- they both add.

A physical description of something *is* the thing?

Let me be more precise and say "the physical simulation", which requires matter in motion according to the physical description (the equations of physics). This is true for software and cats. You've claimed that one cannot describe software by the math of physics; if you're going to be consistent then you'll claim that cats also cannot be described that way. But then I'm interested in what parts of a cat are non-physical.

"Possible" paths that don't actually get executed are mere abstractions, and that means that they don't exist at all (according to you as of five minutes ago)...

I did not say that abstractions do not exist. I said they don't exist apart from matter.

And we've had abacuses that do math for centuries! How silly I was to think otherwise!

Well, yes. An abacus is not a Turing machine. We've only had those (besides ourselves) for less than 100 years.

All I've got to do is come up with a program where Affirming The Consequent and Denying The Antecedent are counted as valid forms of argument. In fact, I think I'll change my brain-software to think that starting... now! Nobody can tell me that I'm wrong, or that I'm just embarrassing myself by committing elementary fallacies unbecoming a toddler with my "fake", "subjective," "made-up" laws that violate the so-called "objective," "universal," "real" laws of logic!

You're right -- nobody could tell you that you are wrong, because your brain couldn't communicate with others who do that. Don't know why you think that's a refutation, since there are humans who do this and are impervious to logic. You can, if you want, argue that, say, the law of non-contradiction is a universal law; but one can equally argue that it's necessary for communication, so that we, as a (mostly) cooperative species hold it to be true since we wouldn't survive if we didn't.

I hate to belabor the obvious, but since no chunk of matter is universal, universals either exist apart from matter or not at all.

It isn't the "chunk" of matter that's important. We can, after all, create NAND gates our of electrons moving through silicon, or photons moving through fibre, or even water moving through pipes. What's important is the way the matter moves and combines. A universal is nothing more than an isomorphism between things in the brain, which is matter moving in certain patterns.

We can test this by considering a case in which knowledge is perfect. For example, that 2+2=4 is to one versed in arithmetic perfectly known. The will has then no latitude (degrees of freedom) in "choosing"/"assenting to" it.

ReplyDeleteEven in this case, though, your will is free in a sense that's denied by Coyne. You come to the conclusion that 2+2=4 because it is rationally inescapable - but that's just it, it's *rationally* inescapable. You're forced to that conclusion by the inviolable deductive logical relationship between the conclusion and the reasons for which you believe the conclusion. The ability to to come to such a conclusion - to be rationally forced to that conclusion - requires the ability to grasp universals and to act based on reasons. So you're free in that your decision is "free" of mathematically determinative laws (though not free of the laws of rational inference).

Off-topic:

ReplyDeleteAfter seeing you mention John Lukac's "At the End of an Age" several times, I've finally purchased a copy. It's really very good! What other works of his would you recommend?

Thanks

@jhall

DeletePretty much anything. In the same vein as At the End of an Age is the earlier The Passing of the Modern Age, which may require some searching to find. There is also The Last European War which is an analysis of WW2 prior to the entry of the USSR and USA. I also enjoyed his exceptionally quirky A Thread of Years, which is one vignette per year for the 20th century, separated by interior dialogues with himself. It ends in 1968, since he has often said that the 20th century was the shortest "century" on record. The Hitler of History examines that topic as it has been understood by historians at different times, and addresses certain problems, such as when Hitler became a virulent anti-Semite.

There are also a series of books on "the duel" between Hitler and Churchill, and one on Hitler and Stalin. His A History of the Cold War was a classic in its time, perhaps the first overview of the Cold War to be written. (It was textbook in our history class.) There is also the eclectic collection The Remembered Past full of essays and excerpts on all sorts of topics. Have fun.

I appreciate the detailed response. Thanks again.

DeleteStrange. For many days I've been unable even to view this entry. I'd try to open it in IE and the browser would (sometimes) show the beginning of the article, but I couldn't scroll of page through the remainder of it.

ReplyDeleteThe formulation here of Free Will is rather Oriental where the essential problem is ignorance, thus salvation is 'enlightenment'.

DeleteDidn't Adam and Eve had perfect knowledge communicated by God Himself?.

Then why did they let themselves be tempted by Satan i.e. why did their perfect knowledge clouded by doubt?. Surely a will to sin is prior to perversion of knowledge?

Edward Feser in Aquinas writes that the will is free to follow intellect or not. So there is a freedom in will that is not related to the indeterminism in knowledge. Also Church says that a well-ordered will follows conscience. Hence a disordered will does not follow conscience.

Ilion, same thing for me. Firefox works, though.

DeleteWhat I have never understood regarding the supposed lack of free will and the consequences thereof is the idea that if it can be proven that people are mere automatons at the mercy of their genes, one would not be able to punish them. Surely one could still argue that not only could people still be punished, but such punishment could be as severe as allowed (ie the death penalty). After all, if one's genes are at fault and one cannot change them, then in the utilitarian worldview, the very existence of such a person does more harm to society than good and if they are indeed powerless to stop themselves committing crimes then the only way to deal with such abominations is to eliminate them (or at least cordone them off from general society).

ReplyDeleteOf course, I don't agree with this (but then, I don't believe we have no free will either) but I find it interesting that no one ever makes this point. Then again, I am not much of a philosopher so perhaps it's a point too woeful for even the Coyne's and Krauss' to make!